“We stand as living monuments,” wrote the historian Len Garrison, of the black British descendants of slavery and empire. “For those who are afraid of who they must be, are but slaves in a trance.” For Garrison, the idea of the African diaspora as “living monuments” was to some extent figurative. But a new book makes it literal. Barracoon: The Story of the Last Slave presents the remarkable fact that there were people alive in America who had experienced abduction from Africa – being examined, displayed, traded and enslaved – well into the 20th century.

The book is the story of Cudjo Lewis; a man born Oluale Kossola in the Yoruba kingdom of Takkoi. Kossola was the last survivor of the last known slave ship to sail from the African continent to America with a human cargo. Written in the 1930s, but hidden away from a public audience until now, it is also perhaps the last great, unpublished work by the Harlem Renaissance writer Zora Neale Hurston.

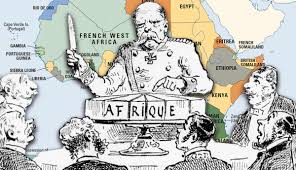

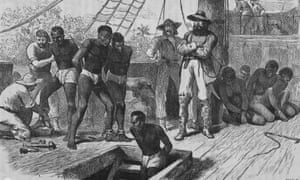

The word “barracoon” refers to the enclosures in which captives were held on the coast before being loaded on to ships. In Kossola’s case it was the Alabama vessel the Clotilda, which played its own gruesome part in the slave trade in 1860, half a century after its official abolition, transporting 130 men and women from the west African kingdom of Dahomey – modern day Benin.

By 1931, when Hurston interviewed Kossola – sweetening him with peaches, Virginia hams and late summer melons –, he was around 90 years old, and yet able, over a period of three months, to recall his life in Takkoi in great detail; his grandfather, an officer of the king; his mother and siblings; law and justice; love and adolescence. He spoke in heartbreaking detail of watching his community annihilated during a raid by Dahomey’s female warriors, leading to his capture and enslavement, the torture of the “middle passage”, and life in 19th and 20th century Alabama. Through all these years – many more lived in America than he had spent in his African birth nation – he never let go of the unspeakable loss of his homeland. When Hurston takes his photograph, Kossola dresses in his best suit, but removes his shoes, telling her: “I want to look lak I in Affica, ’cause dat where I want to be.”

The uniqueness of the story and that of the writer who tells it are layered and intertwined. The old, poetic Kossola, generous with his parables and storytelling, is one of almost four million Africans enslaved late in the history of the transatlantic trade. And while the full history is documented in countless accounts of slave traders, merchants, plantation owners and masters, ledgers and auction records and court documents, the number of first-hand accounts of Africans forced to become Americans can be counted on two hands. It is Hurston, and perhaps Hurston alone, who could have drawn this heavy tale out of the often melancholy old man, and have the vision and skill to make it sing, in the way that Barracoon does, for reasons rooted deeply in her own life story.

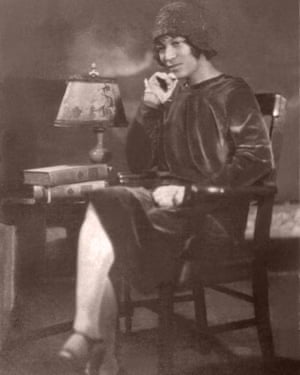

Hurston was born in 1891 in Eatonville, Florida, a small town with an entirely black population, which she would later describe as “the city of five lakes, three croquet courts, 300 brown skins, 300 good swimmers, plenty guavas, two schools and no jailhouse”. She would keep close links to her hometown, despite leaving when she was just 13, and then drifting – working as a manicurist and achieving a degree part time at Howard University – until she arrived in New York in 1925. By then she was in her mid 30s (but convinced those whom she met that she was a full decade younger) and had – as she wrote later in her autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road – “$1.50, no job, no friends, and a lot of hope”.

Hurston began studying anthropology at Barnard College and, having received a fellowship to gather material in her home state, set about documenting African American folk traditions in towns like Eatonville, and later in the southern states, the Bahamas and Haiti. It was during this period, right at the beginning of her career, that she first met Kossola, interviewing him several times in the late 1920s. It was her first major project, but also her first major failure. An article she published about Kossola in the Journal of Negro History would be accused of plagiarism, allegations which scholars now contest, and which in any event drove Hurston to return to Alabama, to conduct the series of interviews that would form the core of Barracoon, and, this time, to do so in a manner that would cast the work beyond any doubt.

Around this time, black art began asserting itself brazenly in an America still emerging from four centuries of slavery and legalised white supremacy, and the belief that the African had no civilisation to offer. By the time of her death in 1960, Hurston would have published more books than any other black woman in America. But it wasn’t until she caught the attention of sociologist Charles S Johnson, champion of the Harlem Renaissance and the editor of Opportunity, the official journal of the National Urban League (which published her work as well as that of Claude McKay, Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen), that she got her break.

Even within the Harlem Renaissance, Hurston’s approach was radical. Inspired by her Eatonville roots, she was instinctively compelled by the folklore, the idioms, customs, worksongs, spirituals, sermons, children’s games, folktales and practices of African American communities of the south. While other members of the black intelligentsia were celebrating racial uplift, and while hundreds of thousands fled the rural south in the “great migration”, in search of what they imagined to be progress in northern cities, Hurston was interested in “the Negro farthest down”. Her goal as an author, anthropologist and essayist, was – the scholar Karla Holloway has said – “to render the oral culture literate”.

“The unlettered Negro,” Hurston wrote, was “the Negro’s best contribution to American culture.” It was this belief which inspired Barracoon – a book in which there is little of Hurston herself, but plenty of her ideology, in capturing Kossola, a man whose culture slavery both created and destroyed. Like the language of some of Hurston’s later works – Mule Bone, the play she would write with Hughes in 1931; Mules and Men, a compilation of oral folklore in 1935; and her most famous work, the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God in 1937 – Kossola’s narrative plays the music of history itself within its tonalities, rhythms and inflections. But the narrative, like Kossola, stands apart from Hurston’s others; his speech is more a recognisably African Creole than the African American vernacular, and despite all his decades living in America, Kossola is steeped in the thought of Africa, the world – as he calls it – “in de Affica soil”. Hurston’s fidelity to the manner and content of Kossola’s storytelling is the book’s strength. Yet within it were also contained the seeds of Barracoon’s downfall. When Hurston took the manuscript to publishers, they wanted her to anglicise his English, which she resolutely refused to do.

“Hurston was not interested in, as Toni Morrison might put it, the white gaze, and how ‘they’ would perceive us,” explains Deborah Plant, a Hurston scholar who edited Barracoon. “She was interested in what was specific in African American culture, those aspects which were rooted in African tradition, African history, African civilisation, because in that authenticity lay the genius – the spirit, as Hurston describes it – that which the soul lives by.”

For Cheryl Wall, Zora Neale Hurston professor of English at Rutgers University, “this impatience with Hurston’s determination to transcribe Kossola’s speech faithfully is enormously frustrating”. It was “part of the pattern of Hurston’s life that she had to fight so hard to have her voice heard, and the voices of those whose stories she wanted to tell. We are told the dialect is too difficult. Is it really any more difficult than the dialect of Mark Twain or James Joyce? Yes it requires some extra effort, but it’s the kind of effort we usually put into a literary text without complaint.”

The irony is astounding. Kossola, a man denied his home and his voice by American racism, would have the telling of his story silenced too. Barracoon, having been met with intransigence by publishers, remained unpublished, ending up in a private collection that was passed to the archive at Howard University in 1956, where it remained inaccessible to all but a handful of scholars who read it and cited it in their work.

Hurston found her own life mirroring this cycle of narration and dispossession. After the success of her work in the 1930s and 40s, her hugely productive career spiralled downwards. She lived hand to mouth, writing articles for magazines while working at odd jobs, including one stint in Miami for an employer who saw her byline in the Saturday Evening Post and tipped off a reporter that the author was her maid. Hurston was humiliated, and spent the next decade in a series of small towns in Florida, plagued by health and money problems, until she ended up in a welfare home where she died, penniless, of heart disease in 1960.

At the time of her death, none of her seven previously published books was in print. Neighbours collected money for her funeral and it made front page news in the local black weekly, the Fort Pierce Chronicle. But she was buried in a segregated cemetery, in an unmarked grave.

For the novelist and feminist Alice Walker, who in 1973 set out to discover what had become of Hurston, finding this grave in a “field full of weeds” was a devastating experience. “There are times,” wrote Walker, “and finding Zora Hurston’s grave was one of them, when normal responses to grief, horror and so on do not make sense because they bear no real relation to the depth of emotion one feels.” Walker was determined to restore Hurston’s legacy and reputation. She obtained a gravestone, and had it inscribed with the words: “Zora Neale Hurston – A genius of the south. Novelist. Folklorist. Anthropologist.”

Their Eyes Were Watching God, still considered Hurston’s greatest work, was soon back in circulation. That edition, by the University of Illinois Press, sold more than 300,000 copies, making it, as Wall says, “one of the most dramatic chapters in African American literary history”.

The publication of Barracoon thus represents a recovery within a recovery; the works of Hurston having been so dramatically resurrected, but this one languishing in obscurity until now. And its publication comes at an emotive moment in the African American experience – an experience loaded not just with historical trauma, but very contemporary pain. Alice Walker writes, for example, in the foreword to the book, that in reading Kossola’s story, African Americans “are struck with the realisation that he is naming something we ourselves work hard to avoid, how lonely we are too in this still foreign land”.

Karla Holloway, professor of English at Duke University, says: “The irony is that the loneliness that echoes through Kossola’s account, and that Walker so poignantly notices, is our collective legacy.

“We work hard to escape and slip past that loneliness, but inevitably we are captured, again, by the wake of slavery, a tidal wash as reliable as moonrise.”

The era of Black Lives Matter, of harassment in coffee shops, of a president who has been both overtly racist and also dismissive of racism, and of the disappointment at the first black president having been able to make little real change to poverty, criminalisation and exclusion, has produced a moment in which the struggle has never been more apparent, yet the cultural expression of that suffering has never been more visible.

“I do think one of the reasons that the book is so attractive right now is that there is this longing for African Americans to have access to a pre-US life – a connection to Africa,” says Autumn Womack, an assistant professor of English and African American studies at Princeton University. “If nothing else, Barracoon announces the desire for this kind of connection, even if it’s never really fulfilled. People are searching for a vocabulary to make sense of that.”

That struggle is finding expression in film, TV and theatre that focuses on the experience of slavery; from the Oscar-winning 12 Years a Slave, the remake of the memorable series Roots and the multi-award-winning musical Hamilton. It is present in pop culture, with the recent phenomenon of Childish Gambino’s “This Is America”, whose video references the violent brutalisation of African Americans. There are new museums – America’s first of African American history, which opened in 2016; the Whitney Plantation, the first plantation museum on American soil; and the nation’s first memorial to the horrors of lynching, in Alabama.

It is abundant in literature too; Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad and other influential books such ass Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, which tells the story of the Great Depression in new and profound detail; Stamped from the Beginning, by Ibram X Kendi, which chronicles the lifespan of American racism; Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, radicalising readers of young adult fiction to the injustice of police killings; and Jesmyn Ward’s devastating Sing, Unburied, Sing.

The pathos of the African American experience, told with such tenderness in Barracoon, is matched by its complexity. Hurston herself remarked that in writing Kossola’s harrowing account of how the king of Dahomey profited from raiding and selling members of neighbouring kingdoms, she was deeply affected by the question of African complicity in the slave trade. “The inescapable fact that stuck in my craw,” Hurston wrote, “was my people had sold me and the white people had bought me. That did away with the folklore I had been brought up on – that white people had gone to Africa, waved a red handkerchief at the Africans and lured them aboard ship and sailed away.”

And yet Barracoon also helps deepen the understanding of the context in which slavery took place. “This idea of ‘African complicity’ is more myth than a reality,” Plant says. “Because at that point in history, there was no such thing as an ‘African’. People on the African continent did not self identify as Africans; instead there was a self identity in relation to specific ethnic groups and specific kingdoms, religions or language. So many of us don’t know, because we don’t have these nuances about our history.”

The absence of stories like Kossola’s has hardly helped bring these nuances to the fore. There are other difficult questions arising from the book about the extent to which the African American victims of slavery internalised the attitudes of their oppressors. Kossola recalls how his children in particular endured bullying from neighbouring African Americans, for having two African-born parents.

“All de time de chillun growin’ de American folks dey picks at dem and tell de Afficky people dey kill folks and eatee de meat,” Kossola recounts in Barracoon. “Dey callee my chillun ig’nant savage and make out dey kin to monkey … It hurtee dey feelings.”

“Those acculturated African Americans could have been more open, more receptive, compassionate, and they weren’t,” Plant says. “They were a source of hostility to Kossola and his community. We can explain or rationalise it, but it doesn’t justify it.” The book’s uniqueness is in its recounting of a story in which we are all equally bound up by this cycle of oppression – the former slave plagued by the trauma of losing his homeland and family, the writer whose work survived the desire of intellectuals for white approval, the reader forced to challenge their own ideas about race and the internalisation of oppression. But more than anything it brings an African past up close to an African American present, at a time of great searching. “Throughout her life, Hurston fought against this idea that there was no connection to Africa once people arrived on these shores, and everything was forgotten,” Wall says. “We know that’s not true. But a book like this really brings that to life.”

• Barracoon: The Story of the Last Slave by Zora Neale Hurston is published by HarperCollins.