How black Americans defy religious stereotypes—and navigate race relations in historically white, European spaces.

This is an appropriate moment for the Church to confront this issue. In August, The Washington Post reported that an Arlington, Virginia, priest named William Aitcheson had been arrested in the ’70s for burning crosses and threatening African American and Jewish families as a member of the Ku Klux Klan—and he never paid restitution or apologized to the victims. More broadly, the Church is increasingly experiencing divisions over politics along racial lines: In the 2016 election, 56 percent of white Catholics voted for Trump, compared to only 19 percent of Hispanic Catholics, according to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University.

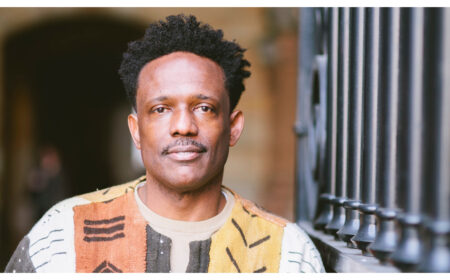

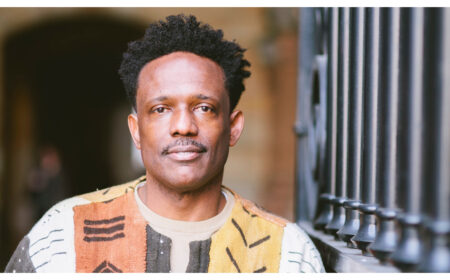

But racial struggles in the Catholic Church are not just about white versus black or white versus Hispanic. Many black Catholics have struggled over their identity in the Church, writes Matthew Cressler, an assistant professor of religious studies at the College of Charleston, in his new book, Authentically Black and Truly Catholic. In the mid-20th century, the big question was how to reconcile the universal message of a Church that claims to transcend race with evidence that it is a “white racist institution,” as activists put it.

This struggle to be “authentically black and truly Catholic” took many forms, Cressler writes. Some African Americans were attracted to the quiet formality of a traditional mass. Others found ways to incorporate African iconography into church spaces: At one “Black Unity Mass” in 1969, Chicago priests stood before an altar draped in a tiger skin and decorated with an African shield.

Emma Green: You write that Americans tend to see Catholicism as a historically white religion. How did that come to be?Matthew Cressler: When I tell people that I study black Catholics, most kind of blink their eyes and go, “What?” We assume Catholicism is European in its essence, and that black people are Protestants. But the majority of black Christians in the Western hemisphere are actually Catholic, and the majority of Catholics in the Western hemisphere and the Americas are not white.

The first black Catholics came to the Americas when the first Catholics came, in the 16th century. But you also have this explosion of black Catholic conversions as African Americans encounter white European Catholics during the Great Migration.

Green: I’m interested in the power dynamics of this encounter. What were race relations among Catholics like during and after the Great Migration?

Cressler: “Tension” is a good word. “Conflict” is a good word. African Americans come to Chicago and other dominantly Catholic cities in large numbers. Neighborhoods that were once white and Catholic become largely black and non-Catholic fairly quickly. White Catholic priests, sisters, and laypeople could leave these big churches behind. They can try to keep black migrants out of their churches—and there’s a movement to do that, where white priests are at the forefront of resistance to black migration.

“What you’ve been doing is training us to be Irish Catholics and German Catholics.”

Green: After this first wave of conversions, there’s a backlash—a movement to recognize the Catholic Church as a “white, racist institution” and create authentically black communities. You almost describe it as a bid to take ownership of traditionally white spaces.

What’s behind this?

Cressler: When white missionaries are introducing Catholicism to migrants, they don’t think they’re introducing them to white Catholicism or Irish Catholicism. They think they’re introducing the one, true, universal Church that transcends race. And the majority of black converts to Catholicism—that’s how they understand it as well.

Over the course of the 1960s, with the rise of the Black Power movement, a small but growing group of black Catholic activists start to look critically at this history and say, “Well, actually, you’ve been telling us that the Catholic Church is universal. But what you’ve been doing is training us to be Irish Catholics and German Catholics.”

Green: This sets up a key identity struggle between a universalistic notion of the Catholic Church and a yearning for a distinctive black identity. How did that play out?

Cressler: This split the black Catholic community down the middle. You have a generation of African Americans who converted to Catholicism because they’re drawn to that claim to universality. And then you have a movement saying, “As black people in America, we can’t be truly Catholic unless we can be our true selves.” There’s a whole range of what that means: integrating African practices and symbols and iconography into Catholic life, or including Afro-Protestant practices like gospel music and liturgical dance.

“The notion of the Black Church … has largely become equivalent to what it means to be black and religious.”

Green: I was surprised by this connection you draw between the Second Vatican Council and the rise of the Black Power movement. Explain that to me?

Cressler: During the first half of the 20th century, you get a rise in the black Catholic population by over 200 percent, and you also have a shift in the center of black Catholic populations from the coastal South to the urban North, where the seeds of the Black Power movement are planted.

Catholics, at the beginning of the Second Vatican Council, are beginning to get more leeway in terms of experimentation in ritual practice. That’s happening at the same time that ideas about what it means to be black are coming to fruition in the Black Power movemen, with people saying, “We are connected to African-descended people from across the world. What it means to be black is to be rooted in this Afro-Protestant, black-church tradition. What it means to be black is to have this distinctively black spirituality.” In the context of the Second Vatican Council, what it means to be Catholic is to integrate those things into Catholic life.

Green: You write that there are 3 million African American Catholics in the U.S., which means there are more black Catholics than members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which would probably surprise a lot of people.

Cressler: The majority of black people in the U.S. who are religious are, in fact, Protestant Christians. And at least in the 20th century, a majority of Catholics in the U.S. were the descendants of European immigrants, although that’s increasingly not the case in the 21st century. So the assumption has some demographic backing behind it.

But in the American popular imagination, the notion of the Black Church—capital B, capital C—has largely become equivalent to what it means to be black and religious. I’m trying to show the dynamism and diversity of black religious life, beyond the boundaries of the traditional black church.

The conflict in this is that, come the 1960s and ’70s, when black Catholics become inspired by the Black Power movement, some black Catholics actually say, “Well, to be authentically black means to be part of the black church.” Black Catholics, over the 20th century, both challenge this notion of the black church as the only way that black people are religious and also ironically reinforce the notion.

“‘Why am I going to leave? This is my Church, not yours.’”

Green: Given all of these identity struggles, why would black people stay in the Catholic Church?

Clements says, “Why am I going to leave? This is my Church, not yours.”

The book is entitled Authentically Black and Truly Catholic, but the notion of authenticity is really operating on both sides of that equation—black and Catholic. What black Catholics like Father Clements would argue is that they are expressing a true and authentic mode of Catholicism. Since Augustine of Hippo, black and Catholic people have always been members of the Church, and the notion that Catholicism is a white religion is a perversion.

Their work is really a work of redemption and salvation, where they’re trying to save an institution that they see as theirs. And they see themselves as having no greater or lesser a claim on it than any other member of the Catholic community.

READ MORE: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/11/black-catholics/544754/