Report: Black men, boys shot most by Chicago police

CHICAGO (AP)

Every five days, on average, a Chicago police officer fired a gun at someone.

In 435 shootings over a recent six-year span, officers killed 92 people and wounded 170 others.

While a few of those incidents captured widespread attention, they occurred with such brutal regularity — and with scant information provided by police — that most have escaped public scrutiny.

Now, after months of struggles with Chicago police to get information through the Freedom of Information Act, the Chicago Tribune has compiled an unprecedented database of details of every time police fired a weapon from 2010 through 2015.

Analysis of that data revealed startling patterns about the officers who fired and the people they shot at.

Among the findings:

•At least 2,623 bullets were fired by police in 435 shootings. In 235 of those incidents, officers struck at least one person; in another 200 shootings, officers missed entirely.

•About four out of every five people shot by police were African-American males.

•About half of the officers involved in shootings were African-American or Hispanic.

•The officers who fired weren’t rookies but, on average, had almost a decade of experience.

•Of the 520 officers who fired their weapons, more than 60 of them did so in more than one incident.

•The number of shootings by police — hits and misses — declined over the six years, from more than 100 in 2011 to 44 in 2015.

The analysis comes at a time when police in Chicago and throughout the country face heightened scrutiny after several controversial police shootings, often of minorities, have been captured on video and gone viral.

The Tribune’s study encompasses high-profile cases such as the McDonald scandal as well as scores of incidents that were not caught on video and received little or no attention. It begins on New Year’s Day 2010 with a teen shot in the stomach while handcuffed to a security fence in the Park Manor neighborhood. It ends six years later, on the day after Christmas 2015, when an officer wounded an armed suspect on the Far South Side.

For years, examining the full scale of the problem in Chicago was impossible because the city refused to release most details about police-involved shootings. Before the release last year of the video of Laquan McDonald’s killing brought pressure for transparency, the only information made public in the hours after a shooting came in comments from a police union spokesman at the scene and perhaps a short statement from the Police Department. As investigations dragged on for months or years, the details remained hidden.

The data on officer shootings were released to the Tribune only after a seven-month battle with the city over its failure to fulfill public records requests. The department finally produced the data in July after the Tribune threatened to sue. Reporters then spent weeks comparing the data with information that was gathered earlier this year from the city’s police oversight agency as well as with other records, including autopsies and court records.

To be sure, policing the city’s most dangerous streets can be harrowing. Nearly 6,000 illegal guns have been seized in the city so far this year — a staggering amount of firepower that far outpaces other big cities. The dangers were on display in graphic detail earlier this month when the department released dramatic dashboard-camera video of officers being shot at while pursuing a carjacking suspect in their squad cars on the South Side. One officer suffered a graze wound to his face.

“As a police officer, you don’t wait for the shot to come in your direction,” Dean Angelo Sr., president of the Chicago Fraternal Order of Police, told the Tribune recently about the database findings. “You might not get a chance to return fire.”

But for many of those who live in the largely African-American communities where police most often open fire, the narrative of self-defense seems like a familiar script.

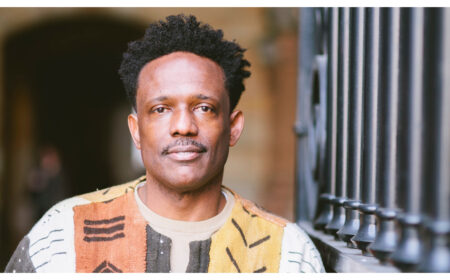

At a recent rally protesting police shootings, Charles Jenkins, a 61-year-old community activist who has spent his entire life on the city’s West Side, said he believes race plays a role in how authorities investigate shootings by police.

“It’s easier to believe, because they’re black, that an officer was in fear of their life and get(s) off,” he said

Those shot by Chicago police ranged in age from early teens to the elderly, the records show. The youngest, Dejuan Curry, was 14 when he was wounded in the leg in August 2015 after police said he refused to drop a weapon he held in his hand as he ran. A federal lawsuit is pending against Victor Razo, the officer who allegedly fired the shots. The Tribune’s records show that Razo was involved in two other shootings between 2010 and 2015.

The eldest victim, Hazel Jones-Huff, 92, was wounded when off-duty Officer Courtney Hill opened fire during a quarrel between neighbors, killing Jones-Huff’s 86-year-old husband. Jones-Huff was charged with battery for allegedly going after the officer with a broom, but a judge later acquitted her of all counts.

The records show the shootings in which a civilian was injured or killed were concentrated in a handful of high-crime police districts, all with largely African-American populations.

Leading the list was the Gresham District, which had 30 police shootings in which someone was injured or killed in the six-year span. Next were two other South Side districts — Englewood with 27 and Grand Crossing with 18. The Calumet and Harrison districts on the West Side each had 17, according to the records.

By contrast, the Jefferson Park and Near North districts, which have majority-white populations, each had four police shootings over the six years. The Town Hall District, which includes part of Lincoln Park, Wrigleyville, the rest of Lakeview, Lincoln Square and part of Uptown, had none, the data show.

The officers who shot

From the data, the Tribune was able to identify the race of 300 of the 324 officers who opened fire in shootings that resulted in injuries or death.

Although white officers make up a larger portion of the police force, they don’t shoot citizens at a higher rate. Hispanic officers, meanwhile, make up only 19 percent of Chicago’s police force but fired in 26 percent of officer-involved shootings.

A little more than half of the officers who fired shots at people were minorities — 84 Hispanics (28 percent) and 69 blacks (23 percent). White officers made up 45 percent of the total — 136 officers in all. The other officers were listed as Asian/Pacific Islander.

The officers also tended to be experienced, not rookies who suddenly found themselves in over their heads. The records show officers who have shot at citizens had an average of about nine years on the job.

Not surprisingly, 87 percent of the police officers who fired their guns in fatal or nonfatal shootings were on duty, the analysis found. Yet that meant 31 shootings involved off-duty officers who wounded or killed people.

Over the six-year period, 520 officers fired a gun at a citizen. The force generally has about 12,000 members. But the Tribune found that 64 of them were involved in at least two separate shootings.

Several of the repeat shooters have been featured in Tribune stories in recent years. At least two of them, Marco Proano and Gildardo Sierra, have been the targets of criminal investigations by the FBI, although no charges have been filed against either.

Proano, who remains on the force on paid desk duty, killed a teenager during a struggle outside a South Side dance party in 2011, then was captured two years later on dashboard camera video cocking his gun sideways and firing into a car full of teens as it drove away, wounding two. Sierra was profiled in the Tribune in 2011 after he was involved in three shootings, two of them fatal, during a six-month span. Sierra resigned from the department last year.

In the past, the Independent Police Review Authority has not tracked officers involved in multiple shootings if the shootings were deemed justified.

Guglielmi, the police spokesman, said the department is now developing an early intervention system to identify and mentor officers who may be at risk, including officers who were recently involved in a shooting or other high-stress situation. The system “will not be designed to be punitive” but will function more as a “risk management” plan to get to an officer’s issues before they manifest on the street, he said.

Officers who have fired their weapons in multiple incidents also avoided public scrutiny in part because the police union contract bars the department from identifying officers after a shooting. In most cases, no information about the officers involved was ever made public unless a lawsuit was filed — and even then the city typically fought in court to keep records sealed.

Meanwhile, the Independent Police Review Authority’s investigations of officer-involved shootings often included testimony and reports from other officers who backed up one another’s accounts — a “code of silence” that has been criticized for years.

In all but a handful of shootings that IPRA investigated over the six-year span, the agency ruled the officers were justified in their use of deadly force.

The Tribune’s analysis showed that Chicago police are the only witnesses listed in most of the shootings, with civilian witnesses identified in just 83 of the incidents.

Alexa Van Brunt, an attorney with Northwestern University’s Roderick MacArthur Justice Center, said it’s often challenging to prove misconduct or a cover-up when it comes to an officer’s word against that of a civilian.

“We don’t have video evidence often,” Van Brunt said. “And if you have police officers lying on reports, that becomes the official record.”

‘He put me in that position’

No officer has fired at citizens more during the time period examined by the Tribune than Tracey Williams, an African-American tactical officer with nearly a decade on the job.

Over five years, Williams fired her gun five different times in various neighborhoods throughout the city — from North Lawndale to Fuller Park, the Tribune analysis shows.

Each time, she fired at a black male. The targets ranged in age from 17 to 45. One died, one survived with a gunshot to the leg and three others were not hit.

The only investigation to capture public attention involved the Dec. 4, 2010, killing of Ontario Billups in the South Side’s Gresham neighborhood.

Billups, 30, was sitting in an idling minivan with two friends in the 8100 block of South Ashland Avenue when Williams and her partner pulled up in an unmarked Chevrolet Tahoe, according to IPRA records.

In a statement she later gave to investigators, Williams said the car looked suspicious so she shined a spotlight into the van and ordered the occupants to show their hands. She was running up to the passenger side of the vehicle with her gun drawn when she said she saw Billups with a “dark object” in his hand.

“He turns,” Williams said. “As he’s turning towards me quickly his hand is coming out quickly with this dark object. I immediately fire a shot.”

Billups was shot once in the chest and died. The dark object turned out to be a bag of marijuana. Even though Billups was unarmed, Williams defended her use of force in her interview with IPRA investigators.

“His actions led to my actions,” she said. “He put me in that position.”

Meanwhile, Williams remained on the street. In one six-month period, from July 2012 to January 2013, the officer fired her gun in three separate incidents but missed. The next year, she wounded an armed 17-year-old boy in the leg. A review of that incident is pending, though most of the records have been sealed by IPRA and the Police Department because the boy was a minor.

In November, the city agreed to pay $500,000 to settle an excessive force lawsuit brought by Billups’ family. That brought the total cost to $643,000 for taxpayers to settle four lawsuits related to Williams since 2010, court records show.

The Tribune’s analysis found that most of the officers involved in multiple shootings over the six years were involved in two each.

Holding a socket wrench

The data compiled by the Tribune show how police calls turned into confrontations — ranging from seemingly benign calls such as trespass or drinking in the public way to extremely dangerous situations such as hostage standoffs or gang shootings.

Police released information about why officers were initially at the scene in 185 shootings over the six-year period. About a third of the incidents — 63 in total — began with officers responding to a report of shots fired or a person with a gun, according to the data. Fifteen shootings happened after police responded to a report of a robbery.

At least 40 shootings began with a traffic or street stop, either because of an alleged violation or after officers stopped and questioned a group congregated in public. In more than a third of the stops, officers gave chase on foot, pursuing suspects through residential backyards, alleys or over fences before opening fire, the data show.

In statements issued by police after the shootings, six of every 10 cited a suspect either pointing a gun or shooting at police as the reason officers opened fire. But of the 74 autopsy reports reviewed by the Tribune, at least 11 showed the shooting victims had been struck only in their back, buttocks or back of the head. The data show police also shot people who wielded other types of weapons, including knives — such as in the McDonald case — but also tire irons, screwdrivers, baseball bats and crowbars. In some cases, the gun police thought they saw turned out to be something else entirely — a wrench or a watch, a cellphone box or wallet.

Georgia Utendhal comforts one of her granddaughters, whose 16-year-old brother was fatally shot by a Chicago police officer in the 8700 block of South Morgan Street in Chicago on July 5, 2014.