The political resilience of the Black-owned bookstore

By Char Adams Feb 6, 2020

When he wasn’t helping some 600 slaves escape through the Underground Railroad, David Ruggles was running a bookstore. In 1828, Ruggles opened a grocery store in New York City and later, as he became involved in the burgeoning abolitionist movement, opened a reading room and a bookstore for Black Americans. It was the nation’s first Black-owned bookstore.

In a building in what is now known as the Tribeca neighborhood of Manhattan, Ruggles sold anti-slavery works and later published the Mirror of Liberty, known as the nation’s earliest Black magazine. This made him especially concerning to slavecatchers and anti-abolitionists, because not only was Ruggles facilitating escapes via the Underground Railroad, but he was also disseminating politically problematic works. Still, he ran a boarding house, reading room, and the bookstore through riots and attacks before leaving New York in 1839. He was repeatedly beaten and jailed for his efforts.

Born a free man, Ruggles was an ardent advocate for abolition. He even helped free Frederick Douglass from slavery by hiding Douglass in his own home. With Ruggles gone from New York, though, his store was no more. But its legacy lived on: His business was the first in a long tradition of Black-owned bookstores with ties to Black political liberation.

“Black bookstores have continuously been hubs for the community to simply be with one another.”

Before Ruggles, the community’s need for Black literature was largely met by Black bibliophiles like him who went to great lengths to collect books, periodicals, and newspapers by Black writers that focused on Black life. Their goal was to make Black literature available to the Black community in reading rooms at a time when Black people were routinely told no books by or about them existed.

Today’s brick-and-mortar Black bookstores continue the legacy of the space that Ruggles created. Black bookshops, owned and operated by Black people, cater to the community with written works by and for Black readers. Many shops also feature a variety of writings by non-Black authors. For all their transformation over the centuries, though, Black bookstores have continuously been hubs for the community to simply be with one another.

Historically, Black independent booksellers have been viewed as the keepers of Black culture. And just as Ruggles’s store allowed him to purvey abolitionist works, many Black bookshops have been closely tied to political movements of their day. Because of this, the stores have long been sites of liberation — and government interest.

“They felt he was running some type of movement here because he was promoting Black culture.”

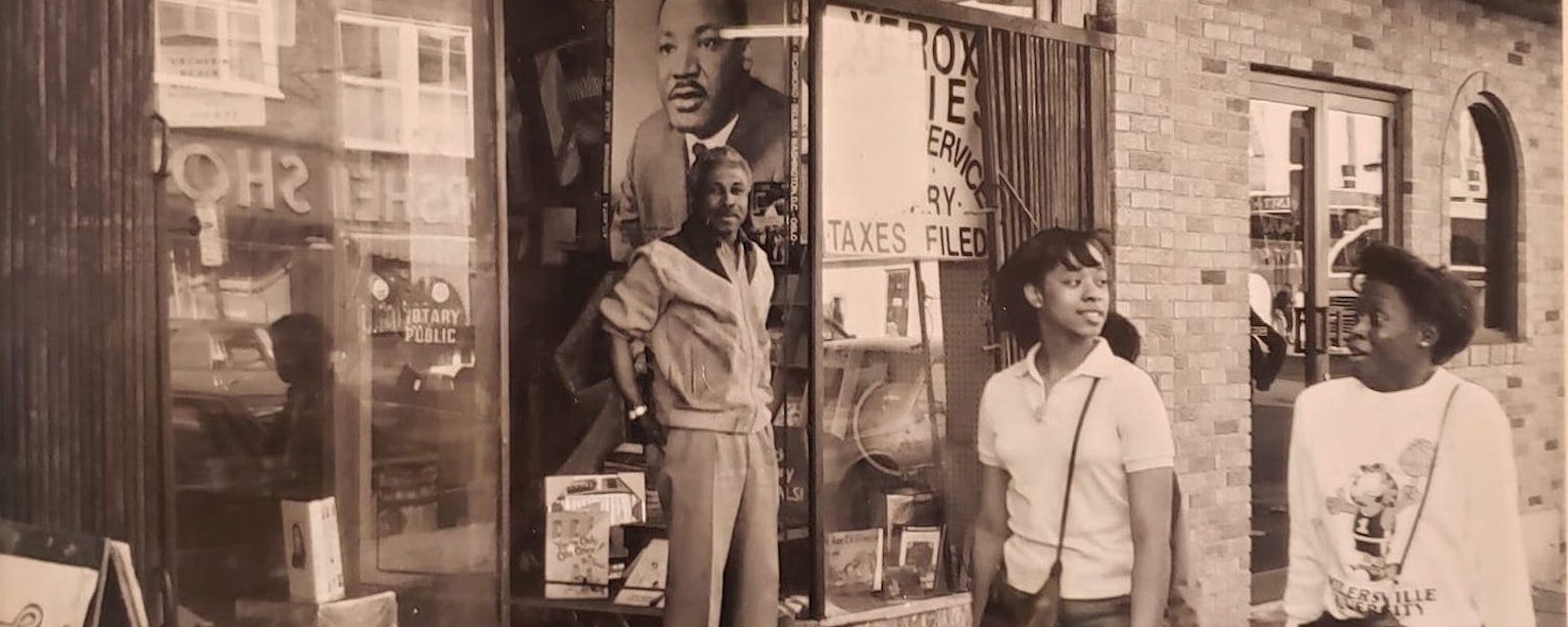

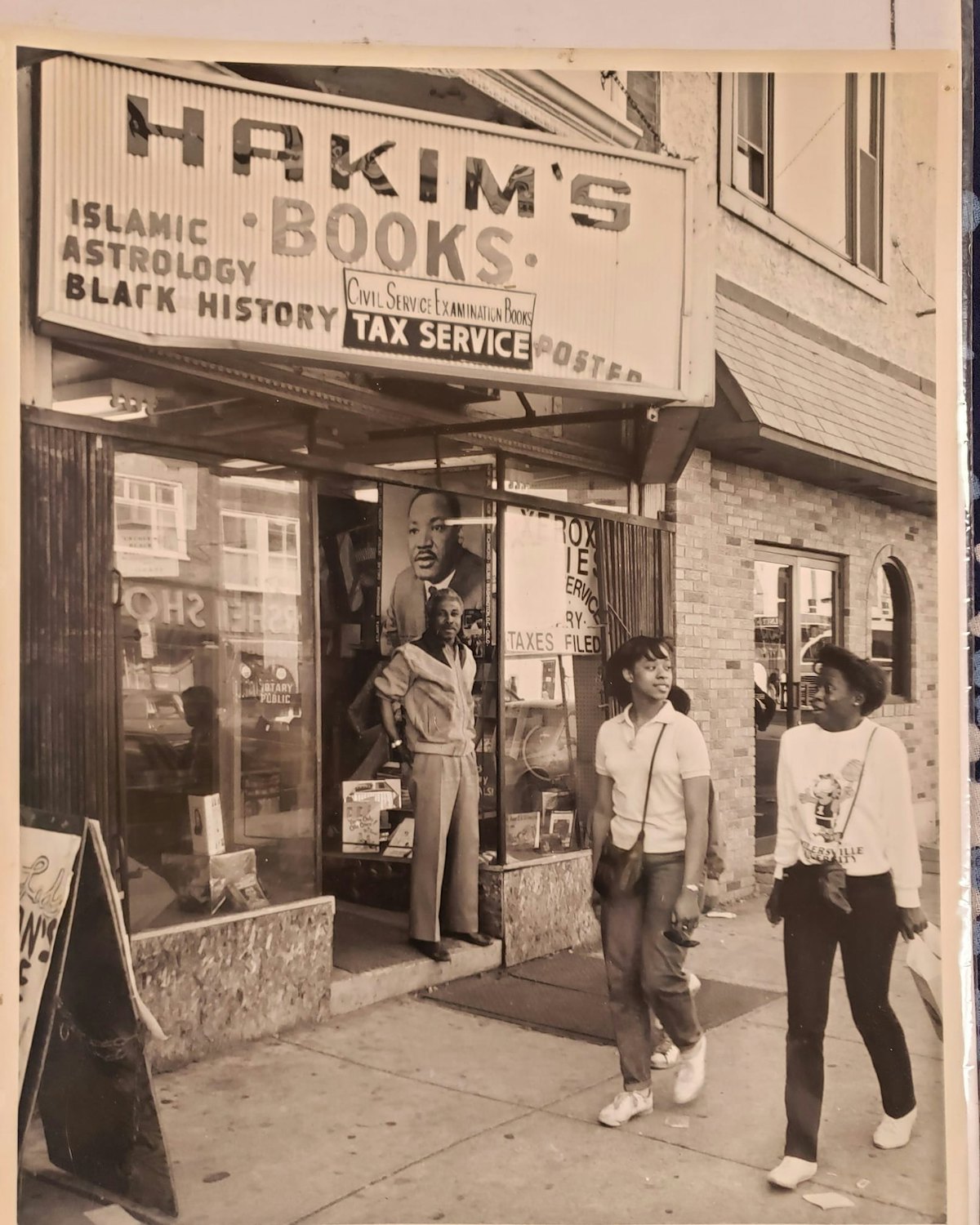

Some of the earliest business owners to follow Ruggles’s example were Lewis Michaux, an outspoken activist who owned the famous National Memorial African Bookstore, a Harlem landmark that opened in the 1930s, and Alfred and Bernice Ligon of the Aquarian Book Shop in Los Angeles, which operated as early as the 1940s and was a stopping place for writers like Maya Angelou and Alex Haley. In the 1960s, more than a century after Ruggles ran his store, the daughter of Dawud Hakim, the owner of Hakim’s Bookstore in Philadelphia, heard her father talk about the FBI agents perched outside his shop.

“People used to stand across the street from the store and take pictures,” Yvonne Blake tells Mic about her father’s store. “They felt he was running some type of movement here because he was promoting Black culture.”

In 1968, then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover ordered FBI outposts across the country to investigate Black bookstores and their owners as part of COINTELPRO, the infamous counterintelligence program that worked to combat the Black Power movement. Each office was ordered to spy on “Black extremist and/or African-type bookstores” to determine whether they served as secret meeting places or hubs for Black extremists.

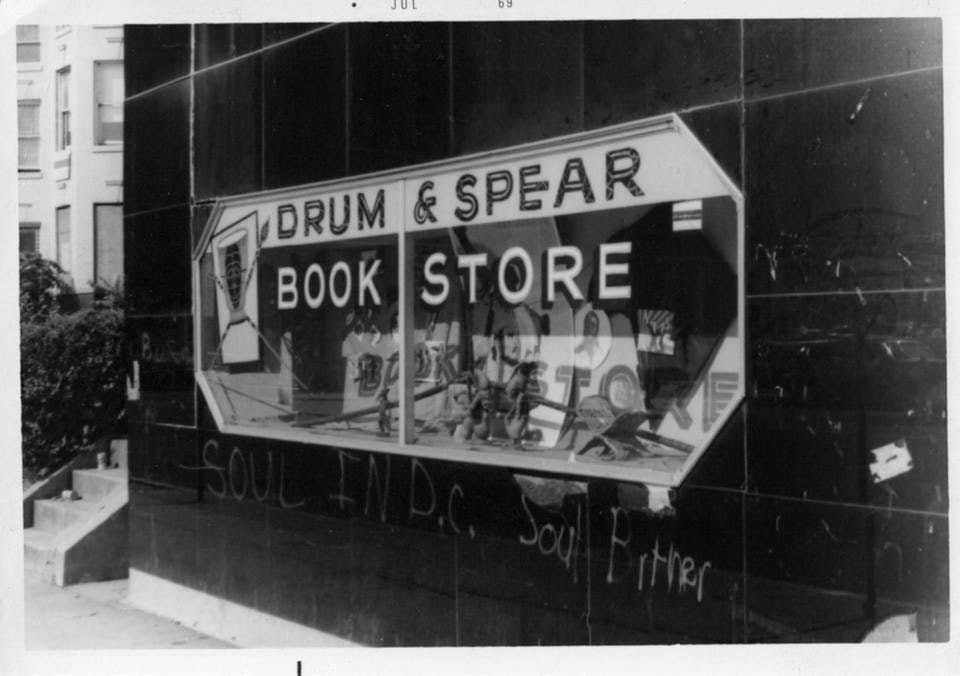

Some 140 miles away from Hakim’s Bookstore, veterans of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a major direct-action civil rights organization formed in the early 1960s, were having their own run-ins with federal law enforcement at the Drum and Spear Bookstore in Washington, D.C. The store quickly became a target for federal law enforcement because of its links to prominent Black activists like Stokely Carmichael. Judy Richardson, an early member of SNCC who worked in the bookstore, recalls a pair of FBI agents visiting the shop.

“It was so obvious who they were,” Richardson tells Mic. “These two white guys, they always looked the same. Very buttoned up, standard-issue shoes. They were buying up Mao’s ‘[Little] Red Book’ and all of the revolutionary literature … to ‘prove’ the case that we were left-wing and to minimize any support we might have in the public sphere. It was an attempt to smear us.”

“They were tracking us,” she continues. “We all had [FBI] files.” The FBI’s monitoring of the group is well-documented, with several files made public by the FBI.

In 1971, Hakim was quoted calling the operation “a waste of taxpayers’ money,” per The Atlantic. “We are trying to educate our people about their history and culture,” he lamented, adding that the FBI should have been pursuing other priorities like “organized crime and dope peddlers.”

“Black bookstores are political spaces. That connection to politics was absolutely essential.”

The feds’ interest in Black booksellers spanned the country. In New York City, booksellers like Michaux and Una Mulzac of Liberation Bookstore were monitored. Edward Vaughn of Vaughn’s Bookstore in Detroit was singled out too, along with the owners of Denver’s Sundiata bookstore. Even Martin Sostre, whose Afro Asian Book Shop was located in relatively lesser-known Buffalo, New York, was under investigation for simply selling Black literature, as University of Baltimore history professor Joshua Clark Davis notes in his book From Head Shops to Whole Foods: The Rise and Fall of Activist Entrepreneurs.

“Black bookstores are political spaces,” Davis tells Mic. “That connection to politics was absolutely essential to these bookstores. So many Black activists, so many Black people who started bookstores in the ‘60s and ‘70s, the vast majority of them came out of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. You have folks who come out of movements and start bookstores. That’s a pattern that repeats itself.”

The late ‘60s marked a sharp increase in Black independent bookstores, and the timing of the surge — during the height of the Black Power Movement — was no coincidence. Hoover was right about one thing: Black bookstores were gathering places rooted in activism. But they went far beyond politics, too. These shops catered to the community and provided a space for Black people to come and not only read, but also talk about what they read. Chester and Lillie Owens and James and Dorothy McField, two Black couples, understood this full-well when they opened The Hub in 1965 in Kansas City, Kansas. They served tea and gourmet foods to those who came to the bookstore to simply hang out, and sold African clothing and jewelry, according to Kansas City-based NPR affiliate KCUR.

“[It was about] the young people who would sit down on the floor of The Hub and read the books,” Chester Owens told KCUR in October. “[Profit] had nothing to do with it.”

The number of Black bookstores dwindled along with the Black Power Movement in the mid- to late-’70s. And the dismal economy of the decade only led to more closures. However, in the ‘90s, major Black cultural and political moments — like the Los Angeles Riots, the Million Man March, and hip-hop’s golden age — led to a sharp increase in such stores.There was a renewed interest in Black history, especially after New York’s Howard Beach killing in the late ‘80s and a series of fire-bombings at southern Black churches in the ‘90s, according to the Los Angeles Times. Major bookstore chains took notice and ramped up their African-American book offerings, the Times reported then. But the variety and culturally specific titles that the major retailers lacked, Black independent bookstores offered to literature-thirsty Black communities.

“It was a vehicle for people looking for new ideas and thoughts from a Black or African-centered perspective.”

Akbar Watson, director of the Boynton Beach, Florida-based Pyramid Books, launched his shop in 1993 after he and his friends grew tired of having little access to books by Black writers and about Black life, academia, and culture.At the time, he says, “reading was hot.”

“It became political,” Watson tells Mic of his store. “I didn’t start [the store] to become political, but I was housing [books] with universal issues that catered toward Black people. It was a vehicle for people looking for new ideas and thoughts from a Black or African-centered perspective. The customers demanded that. It quickly became political because it was part of the business. It’s what people wanted.”

The number of Black bookstores peaked with at least 200 in the mid-‘90s, Davis says, before plummeting over the years to just 54 in 2014, according to the African American Literature Book Club. The number slightly recovered to reach 70 in 2016, per the database. When you put those numbers in context, you realize how precarious the situation was for Black bookstores: The Open Education Database notes that independent bookstores overall endured a precipitous drop too, thanks to the rise of Amazon and major chains — from more than 4,000 independent stores in the early ‘90s to just 1,900 by 2011.

But now, yet another revolutionary political climate has resulted in a new wave of Black-owned bookstores, even as brick-and-mortar bookstores struggle in the shadow of online titans like Amazon. Today, the African American Literature Book Club estimates that about 120 Black-owned bookstores are operating in the U.S.

“People are realizing bookstores offer something special,” Davis says, crediting “everything from Obama’s second term and Trayvon Martin to Black Lives Matter and Black Twitter” for drawing increased attention to racism and injustice and fueling an uptick in interest in Black life.“Black bookstores are uniquely positioned to serve citizens who want to learn more about Black history and culture or learn about racism,” Davis says.

Of course, the books are part of the appeal, too. The latest increase in Black bookstores may also be due in part to the “huge number of excellent new Black authors,” Davis says. Writers like Tressie McMillan Cottom, Brittney Cooper, Roxane Gay, and Kiese Laymon have produced works that fly from the shelves and spark meaningful conversations, Davis says, and Black bookstores have long been a stopping place for Black writers promoting their work.

“Whatever the country is going through, the Black community is feeling it 17 times harder.”

Still, bookstore ownership is known as one of the most challenging plights in retail. Many of the stores still in existence have relied on monetary help from their communities. Blake, who still runs her father’s store in Philadelphia, has turned to crowdfunding sites like GoFundMe to keep the doors open. Other shops, like Seattle’s Life Enrichment Bookstore, have done the same.

This was also the case for Noëlle Santos, the owner of The Lit. Bar in the Bronx, New York. Despite having no bookselling (or retail) experience, she stepped in to fill a void after the neighborhood’s only bookstore — a Barnes & Noble — closed. She used her social media prowess and several pop-up shops to establish the Lit. Bar name before opening the store in 2019.

“Whatever the country is going through, the Black community is feeling it 17 times harder,” Santos tells Mic. “It’s not that we lack the talent — we lack the investments. We have to go out and get it.”

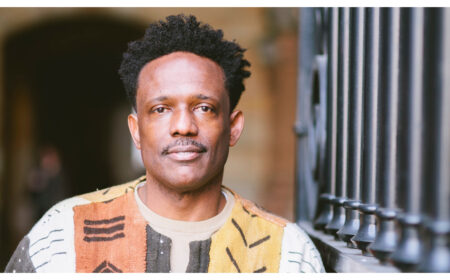

Santos’s shop includes a wine bar, and she additionally holds offsite events and even provides textbooks for nearby schools. Her model is similar to the one that held up Black bookshops in decades past. Just as Lit. Bar provides a space for the community to gather, so does Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee & Books in Philadelphia (owned by Marc Lamont Hill), WORD in Brooklyn, and many more.

While we enjoy this most recent wave of Black bookstores, it’s hard not to wonder whether some new pressure — political, social, or economic — will once again diminish their number. But if history has taught us anything, it’s that these shops are as resilient as the people who occupy them. Santos, for example, sees her business not as an entry in history but as an investment in what’s to come.

“I never thought about making my mark on history. That never registered,” she says. “I’m thinking about the future and how much impact I can make.”

READ MORE AT: https://www.mic.com/p/the-political-resilience-of-the-black-owned-bookstore-21738486