WE MUST NEVER FORGET!!!

JOSEPH BLACKBURN BASS 1863 – 1934

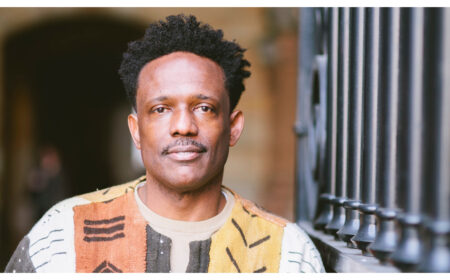

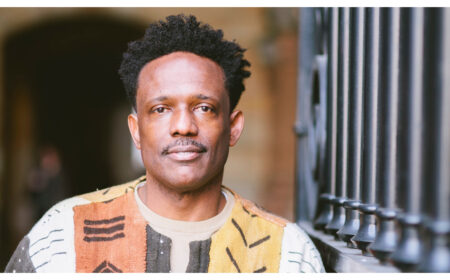

Joseph Bass was born in 1863. He was an African American teacher, businessman and newspaper editor.

From Jefferson City, Missouri, Joseph Blackburn Bass taught school for seven years but in 1894, William Pope, editor of the Topeka Call offered him the job of newspaperman. In 1896, Pope died, and Joseph Bass became owner, publisher, and editor. In 1898, Nick Chiles purchased the newspaper and changed the name to The Topeka Plaindealer. J.B. Bass worked as Chile’s associate until 1905 when he moved to Helena, Montana to establish The Montana Plaindealer. Bass wrote, edited, and published the Plaindealer at 17 South Main Street in Helena, aided by an assistant, Joseph Tucker, from March 1906 to September 1911. An activist and promoter of civic organizations, Bass embraced progressive political goals and urged Helena’s sizable African American population—more than 450 in 1910—to be entrepreneurial and engage in cultural uplift. In 1906, Bass helped organize the St. James Literary Society, based in the St. James AME Zion Church. Three years later, Bass spearheaded the Afro-American Protective League, an ambitious statewide organization that meant to defend African Americans in Montana from racism. The group lasted only a few months, but Bass had established himself as a community leader. Two years earlier, in 1907, he helped organize a Helena chapter of Booker T. Washington’s National Negro Business League, which included more than a dozen businesses in town, and in 1908 Bass created the Afro-American Building Association, a self-help group of African American real estate owners in Helena.

In 1911, he went to San Francisco for one year, then on to Los Angeles for a brief visit around October 1912. J.B. Bass decided to stay and in late 1912 he paid a visit to the California Eagle, which was on 1328 Central in L.A. In 1913, Charlotta Spear hired J.B. Bass to do a limited amount of newspaper work, including running the newspaper for two weeks while she traveled north. At the end of 1913, she offered Bass the position of editor of the Eagle, they married in August 1914.. Joseph Bass held that position until his death in 1934.

An excerpt from Charlotta Bass’s column, “On the Sidewalk,” dated April 2, 1937, reads: “My last visit Sunday was to the grave of the late editor of this paper, J.B. Bass. I did not lay a large bouquet upon the grave of him who sleeps beneath, but gardenias three in number, with their fragrance mild but sweet, conveying a message I cannot here repeat.”

“Together we started,

“Together we parted,

“He sleeps, and I go on with the task, he would have me complete.

“Fellow traveler, I do not ask for a lift–

“I can carry my load.

“I only ask that you do not block my path.”

Reference:

Black Past,Joseph Bass

CHARLOTTA A. BASS 1874 – 1969

Was an African American educator, newspaper publisher-editor, and civil rights activist. Bass was probably the first African-American woman to own and operate a newspaper in the United States; she published the California Eagle from 1912 until 1951. She used her influence as the publisher of a newspaper to uncover injustice and fight for civil rights.

Bass was born Charlotta Amanda Spears in October of 1880 in Sumter, South Carolina. She was the sixth of 11 children between Hiram and Kate Spears, but very little is known about her parents or her early life. Bass moved to Rhode Island soon after graduating from high school, and found work selling ads and doing odd jobs at a newspaper. She grasped the nuances of the business over 10 years of employment at the Providence Watchman. After moving to Los Angeles, California, in 1910, she found work selling subscriptions to the African American newspaper the Eagle.

Two years later, the Eagle’s publisher, J.J. Neimore, took ill and asked Bass to take over the operation of the paper upon his death. The surprise bequest made Bass the first African American woman to run a newspaper in the United States. However, the Eagle was in dire financial straits when she finally assumed the role of editor and publisher. Determined to correct the paper’s course, Bass changed the name to the California Eagle, and began hiring staff that were less interested in society reporting and more dedicated to reporting on the issues of the day. In 1912, she hired Joseph Blackburn Bass to be the paper’s editor. Bass had been one of the founders of the Topeka Plaindealer. He shared his concern with Spears about the injustice and racial discrimination in society. He eventually became Bass’ husband and they ran the newspaper together.

By 1915, the paper was staking out firm political stances. Bass ran editorials denouncing D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, a film that many found offensive for its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan and ideas of white supremacy. Bass’ protest motivated African American newspapers around the country to join her in condemning the film. When she realized the true scope of influence the media possessed, Bass redoubled her efforts to use the Eagle as a tool to fight for the rights of African Americans. The paper tackled issues such as fair access to housing, segregated schools, and illegal hiring practices by corporations. The Basses powerfully championed the black soldiers of the Twenty-Fourth Infantry who were unjustly sentenced in the 1917 Houston race riot. They also covered the case and supported the “Scottsboro boy,” nine young men who were framed and convicted of rape in Scottsboro, Alabama in 1931.

During the 1920s, Bass became co-president of the Los Angeles chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, founded by Marcus Garvey. Bass formed the Home Protective Association to defeat housing covenants in all-white neighborhoods. She helped found the Industrial Business Council, which fought discrimination in employment practices and encouraged black people to go into business. As editor and publisher of the California Eagle, the oldest black newspaper on the West Coast, Charlotta Bass fought against restrictive covenants in housing and segregated schools in Los Angeles. She campaigned to end job discrimination at the Los Angeles General Hospital, the Los Angeles Rapid Transit Company, the Southern Telephone Company, and the Boulder Dam Project.

By the mid-1930s, the Eagle was in solid financial shape, and with a circulation of 60,000, was the largest African American newspaper on the west coast. Her husband’s death in 1934 was an emotional blow to Bass, and a key transitional point in her life. When she recovered from grieving, she began to dedicate herself to political activism beyond the newspaper. Bass worked diligently on the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign that urged African Americans to take a personal stand against discriminatory hiring practices, and only spend their money at businesses that hired, or were run by, African Americans. Soon, she began to consider the possibility of running for public office.

After rallying a group of black leaders in a battle against Los Angeles mayor Fletcher Bowron, Bass became convinced that politicians were not representing the issues that were important to the people. Although her group was successful in pressuring Bowron’s office to expand its Committee on American Unity, none of its other demands related to racism and discrimination were addressed. In 1945, Bass ran for Los Angeles City Council, and in 1950, became the Progressive Party’s candidate for state senate. She didn’t win either race, but gained a taste for politics and a platform for voicing ideas provided by political debate among candidates.

Because Bass’ political rhetoric was decidedly leftist as the United States entered the McCarthy era, and as suspicions toward communists, intellectuals, and activists reached a fever pitch, she found herself under surveillance by the FBI. In 1950, she was called before the California Legislature’s Joint Fact-Finding Committee on un-American Activities. Though neither Bass nor her paper were found guilty of any wrongdoing, she was subjected to surveillance for the remainder of her life. This did little to slow her political ambitions, however, and in 1951, after nearly 40 years as the managing editor and publisher of the Eagle, Bass sold the paper and began preparations for what would be her greatest challenge. Bass served in 1952 as the National Chairman of the Sojourners for Truth and Justice, an organization of black women set up to protest racial violence in the South. Also In 1952, she ran for vice president of the United States on the Progressive Party ticket with Vincent Hallinan. She did not aspire to win, but rather to broadcast her views into a more public and national forum with a motto of “Win or lose, we win by raising the issues.” The bid for the vice presidency made Bass the first African American woman to run for a national office.

Despite her splashy appearance on the national stage, Bass continued to be dedicated to political work in and around Los Angeles throughout the remainder of her life. She never saw the city become the place of racial harmony that she envisioned, but during Bass’ life, Los Angeles was one of the most progressive cities in the United States, due in great part to her own efforts. When Bass moved just outside of Los Angeles in 1960, to Lake Elsinore, she opened her own garage as a community center and reading room. She hosted voter registration drives and became a regular participant at local protests against South African apartheid policies and on behalf of prisoners’ rights.

Throughout her journalistic and political careers Bass fought for the rights of African Americans across a range of practical issues. In the course of her work, she befriended the famous activists Paul Robeson and W.E.B. Du Bois. Although Bass never was elected to public office, she was successful in her attempts to galvanize national energy around discrimination and civil rights.

In 1966, Bass suffered a stroke that confined her to a convalescent home. On April 12, 1969, she suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died in Los Angeles. She is buried alongside her husband in Evergreen Cemetery, East Los Angeles, California.

blackpast.org