Trauma and Poverty Alters the Brains of Black People, and It Will Take Black Institutions to Stop It

By David A Love

The shame is not ours. That holds true of the horrors and the trauma of the Middle Passage, and the toll it exacted on the bodies and psyches of African people. And that applies to the continued racial oppression, the deprivation and the economic, physical and mental violence to which Black people are subjected every day. While white society has told Black people that their “problems” are of their own making, a result of their moral failures and lack of work ethic, white America promoted this false narrative by punishing Black folks through public policy.

What if the shame is indeed not ours? What if neuroscience, the study of the brain, can make sense of the effect of trauma on the very minds and behaviors of Black families, adults and children? What if white supremacy takes its toll on the health and development of our minds, not just in a philosophical, political or cultural sense, but from a medical and scientific standpoint?

If the problem is one that Black people face, then Black institutions will solve it. For the first time, two African-American organizations — a health services agency and a fraternity — are teaming up to address the neuroscience of poverty and the impact of trauma on the Black mind and behavior.

The Columbus (Ohio) Area Integrated Health Services, Inc. (CAIHS) and the Columbus Kappa Foundation, Inc. — part of the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity — have formed a partnership called the Global Life Chances Initiative. The project will provide services, education and outreach to Black families hit the hardest by infant mortality, educational under-performance and economic dislocation. Further, through a concept known as the neuroscience of poverty, the initiative will address prevention and repair of Black people traumatized and damaged by economic deprivation and exploitation and the toll poverty has on the brain.

The concept represents a bold and innovative research approach. Past studies have examined inter-generational trauma and post-traumatic slave syndrome, and the ways in which the psychic damage of enslavement, genocide and other forms of oppression can be passed down through generations.

A recent Newsweek article addressed how poverty impacts the brain. Specifically, it said that “poverty, and the conditions that often accompany it — violence, excessive noise, chaos at home, pollution, malnutrition, abuse and parents without jobs — can affect the interactions, formation and pruning of connections in the young brain.”

“This is an important initiative for this historically African-American mental health organization. For decades, we have witnessed clients that our agency has provided services for suffer from trauma and issues that professionals have found difficult to treat,” Penn told Atlanta Black Star. “When you look at the high rate of infant mortality in Columbus, the parents that are impacted by high infant mortality, there is a large [amount of] depression and need for support to those families.”

Penn added that it is important for the African-American community to move beyond these long-term issues that hold our community back.

As Nate Jordan II, President of the Columbus Kappa Foundation, Inc. noted, the new initiative will be based in the Mount Vernon section of Columbus, where the Kappa House is located. Jordan told Atlanta Black Star that Mount Vernon is “one of the most economically depressed areas from redlining. A lot of abandoned housing, all of the detrimental things are exemplified in these housing areas.”

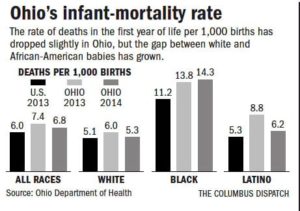

“In Ohio, the Black infant mortality rate is 48th in the country. In Columbus, the Kappa House is in [an area with] one of the highest infant mortality rates in Ohio, where there are seven hot zones” for infant mortality, he added. Jordan noted that the Kappas became involved in the Global Life Chances Initiative through their engagement in infant mortality, safe sleeping issues and matters concerning Black fatherhood.

“We also looked at the father missing out of the family unit and how the father can make a big difference from an infant mortality standpoint…even when the baby is still in the placenta, having the father acting from a nurturing standpoint,” he said.

Jordan also mentioned the Kappa’s Nurturing Fathers program, an evidence-based, 13-week program in California that improves life chances for children and puts fathers back into the lives of their families. A group of 10-16 fathers receives services and education around their relationships with their child, the roots of fathering, nurturing, discipline without violence, anger management, nutrition, housing and other issues.

“We’re Black men showing leadership, and we already have a tremendous following. We’re politically in position, and people are looking for our leadership. So this is another example of the Kappas being on the front burner, and this model we’re putting together will be going nationwide,” Jordan noted.

For Dr. Stacy Scott, a consultant with the National Kappa Foundation’s Healthy Kappas/Healthy Communities National Initiative, this new partnership makes sense.

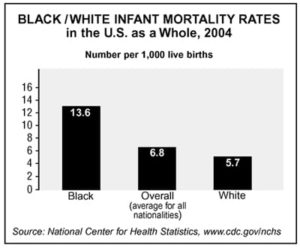

“I work in the infant mortality field, and we know the impact of stress on African-American women and the impact on their outcomes. We know African-American women have the highest rate of infant mortality, with 14 African-American babies dying for every 1,000 — 6 for white babies, so that is double,” Dr. Scott told Atlanta Black Star.

“We see a lot of babies who die because they are in unsafe sleeping environments,” she noted. “We are in the process of training Kappa membership to go out in the community to target specifically men on safe sleep practices for infants. It is growing; it is amazing when you start teaching men. When men are involved in prenatal care, especially in the first 3 to 4 weeks, we see how infants thrive,” Scott added.

Two issues that concern the participants in the Global Life Chances Initiative are the trust of the Black community, and the stigma over mental illness among African-Americans.

Two issues that concern the participants in the Global Life Chances Initiative are the trust of the Black community, and the stigma over mental illness among African-Americans.

“That whole trust issue, that’s why it is so important that the partners look like the community we’re servicing,” Dr. Scott said. “A predominantly African-American membership is important because there is that mistrust. We know because of the Tuskegee fiasco,“ she noted,  adding it is important “to have key people and key researchers who look like our community and build that trust so that people will not be exploited. There is such a disproportional representation of communities of color with health disparities, and it turns into an indictment of a particular group. And it is not an indictment, but reflects discrimination and segregation, and so I think it is going to be a slow-moving train” she said, noting that it all adds up to getting the message out one person at a time.

adding it is important “to have key people and key researchers who look like our community and build that trust so that people will not be exploited. There is such a disproportional representation of communities of color with health disparities, and it turns into an indictment of a particular group. And it is not an indictment, but reflects discrimination and segregation, and so I think it is going to be a slow-moving train” she said, noting that it all adds up to getting the message out one person at a time.

“It is a fresh new phenomenon. and the community is ready. And we are tired of ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps,’ ” Scott added. “Maybe it is not something wrong with me, and I am a victim of racism.”

“On a national level, 1 in 5 people are impacted by a mental health condition, and we know that stigma and overcoming the stigma is real. But this is an awareness campaign we are launching to understand how to reach our community, how to make service delivery culturally sensitive, to take into consideration the historic stigma our community has faced with mental health issues, and neuroscience. So, that is part of our relationship with the Kappa Foundation, a fraternity that is well respected, and we go to the grassroots and find ways to be more effective,” Penn noted. “Through education, through door-to-door outreach and having culturally competent delivery providers, we know we’re going to have more of an impact than what has been historically done.”

According to Penn, often there is a lack of understanding of how to work with the Black community. The Global Life Chances Initiative hopes to provide a blueprint for upliftment though outreach to the community and addressing a serious condition. Given “the stigma that is associated with mental health issues, I personally want to see our organization and the Kappa Foundation be the institutions that lead this movement to make it easy for families, for individuals, for people of color, so that it is easy to come in and get help when I need it, to seek treatment when I need it. I don’t need to mask and hide the symptoms; I can come in. The same way you feel comfortable calling the doctor when you have a headache, people with mental health issues can find it easy to come in and ask for help,” he said.

“When you say ‘I am not quite right,’ I can give you a reason why I am not quite right,” Dr. Scott noted of this planned research. “It does give you another tool, and if we put it out there right, people begin to get a better understanding in regards to why we are the way we are. For example, why do so many African-Americans have high blood pressure? It gives some foundations as to why the community has such plights,” she said. “If you look at the brain and things of that nature, they want to blame the victim, and the idea that if we give you a pill and some job training, you’ll be OK.”

Meanwhile, the undertaking has serious implications in the public policy realm, with the potential to change the status quo.

According to Dr. Linda James Myers, Professor of Psychology, Psychiatry and African-American Studies at The Ohio State University and Director of The Ohio State University Black Studies Extension Center in Columbus, Ohio, the neuroscience of poverty provides a social context for what is affecting the Black community. She argues that Western science, for instance, is not holistic, and fails to make the necessary connections between one’s environment and physical and mental well-being.

“A more African-centered perspective assumes that what happens in my physical environment will affect my behavior and my chemistry, and that constant stress will affect every aspect of my physiology, including the brain,” Dr. Myers told Atlanta Black Star. She added that this more holistic and integrated African-centered perspective is nothing new. Further, a holistic world view and a cultural frame of reference that was previously missing will allow us to counter the notion that poverty is the result of Black people making bad decisions.

“One of the big things that we want to concentrate on in the first phase is to educate the decision makers that make policy, allocate funding, educate them on this work that we are undertaking,” Penn said. “What is different about this partnership that does not exist anywhere else in the country is that you have a unique partnership, with an integrated strategic approach on how to lay out a plan of dealing with the history of trauma that African-Americans have dealt with for decades. We have a strategy to begin to ask the questions and explore the research on how to better serve our community,” he noted.

“We know the issues exist, and there has been a system of a continued way of treating the problem, continuing to fund a certain model, but we’re looking at how do you, with scientific data, change the direction that we find many of our young people, many of our adults, living in poverty? How do we change the infection and change the cycle? We don’t want to lead by emotion, but we want our emotion to be inspired by research. It will benefit not only our community but all communities,” Penn added, as the program will be emulated nationwide.

“White folks won’t believe it unless it is researched,” Dr. Scott suggested, offering that the program has the potential to upend policies such as the welfare system, which is based on the premise of a work ethic. People in welfare-to-work programs are set up to fail, she noted, and people are punished as if it is a reflection on them. What happens, for example, when it is discovered they cannot perform certain work functions because of trauma.

“If there is long-term impact of trauma on the brain, that debunks the whole argument,” she concluded. “It is really going to challenge the status quo, and looking at all these acts and the welfare system, you can make an impact because what they’re doing is not working, and there is going to be a lot of fallout, because people don’t like change,” Scott said. “You don’t hear them talk about research and African-Americans with regard to this theory. This might be on purpose, because we would have another tool to say we want our 40 acres and a mule.”

Once the word spreads about this new initiative, Dr. Scott believes, it is going to be phenomenal. However, she provides a warning: “We have to be very, very careful to make sure they don’t use this against us. We have to advocate, because if they think we have a brain dysfunction they will write us off. It is important to make sure advocacy groups are on the case, because it is not our fault.”

“One of the advantages with this initiative is trying to get the powers that be to see that what is different about what young Black people are experiencing in poverty today — from what young Black people experienced back in the day with chattel enslavement and sharecropping — is the role of the community, despite the poverty,” said Dr. Myers. “Now we have urban renewal, our community has been fractured and displaced, our people were placed in public housing — which is not good for our community as it produces anger and frustration — and now without the community to support and without the educational system you have complete disenfranchisement. You have dislocation and generalized depression. Instead of asking what is wrong with these young people, we should ask: What is happening and how can we change it?”

“The fact that we see the physiological change because now we have the technology to monitor it has principal benefits and also great costs. The benefits mean that Western researchers must concede that these children are in a demeaning, disenfranchising environment that affects their brain. Maybe that means we not only need early literacy but to be more holistic in what children are experiencing. That awareness is coming is a good thing. Unfortunately, it has taken a long time to come to that realization,” Dr. Myers offered. “The downside is, ‘Oh my God, these Black children are deficient.’ They are open to being stigmatized, and the Black community is going to be further disenfranchised. We have to make sure that the people engaged in the research will not go that route,” she added, noting the evidence that the condition is not irreversible. “The evidence is the 250 years Black people spent in enslavement. I can’t think of a more hostile environment. Then you see Black people emerging out of chattel slavery making all the contributions to the industrial and technological revolution,” she added.

Meanwhile, Jordan reflected on the importance of having Black organizations step up to tackle this issue in the Black community, rather than rely on white society.

“No longer can we depend on them to solve our problems. We have the expertise, the talent, the facilities and the ideas. We live this. We are the ones who have been here 400 years, and we are going to get it solved.”