Memorial for the Thousands of Black Lynching Victims in America Opens Next Year in Montgomery

The organization will also announce plans to open a museum called “From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration” in its 11,000-square-foot headquarters in April 2017. Located in a former slave warehouse, the museum will chronicle the nation’s racial history from the days of slavery to mass incarceration, and like the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, to grapple with our legacy of racism and understand the connection to the present.

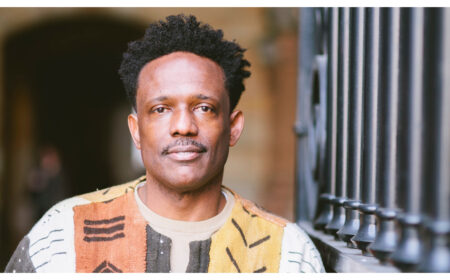

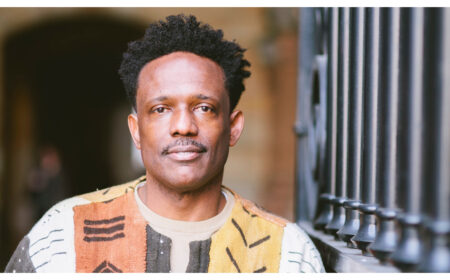

“Our goal isn’t to be divisive,” Bryan Stevenson, the director of the Equal Justice Initiative, told the Times. “Our goal is just to get people to confront the truth of our past with some more courage.”

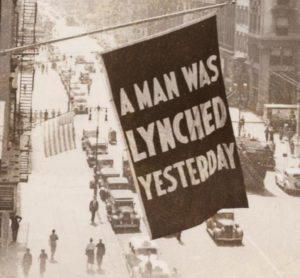

In 2013, Stevenson’s group placed markers throughout Montgomery detailing the city’s history as a slave market. As The New Yorker reported, while the city had dozens of cast-iron markers referencing its Confederate history, there were none to indicate the presence of the slave trade. And last year, the group released a report called “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.” The report documents 4,075 lynchings of Black people that took place in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia between 1877 and 1950.

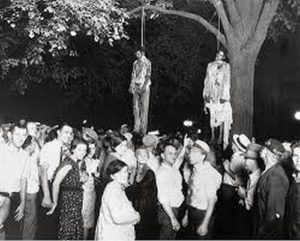

The report discovered several hundred more lynchings than were previously known, and that many of the victims had not been accused of a crime. Rather, “racial terror lynching” was designed to maintain the racial control of Jim Crow segregation by victimizing the entire Black community. Moreover, they were celebratory affairs and horrific “public spectacles” in which the entire white community attended, and no one was held accountable. Lynching was a major impetus leading to the forced migration of millions of African-Americans to the North, and yet there is little effort to address what took place.

According to the report, these lynchings were acts of terrorism “because the murders were carried out with impunity, sometimes in broad daylight, often ‘on the courthouse lawn.’ ” As opposed to so-called “frontier justice,” these killings took place in communities with a viable criminal justice system regarded as “too good for African Americans,” according to the report:

“Large crowds of white people, often numbering in the thousands and including elected officials and prominent citizens, gathered to witness pre-planned, heinous killings that featured prolonged torture, mutilation, dismemberment, and/or burning of the victim. White press justified and promoted these carnival like events, with vendors selling food, printers producing postcards featuring photographs of the lynching and corpse, and the victim’s body parts collected as souvenirs. These killings were bold, public acts that implicated the entire community and sent a message that African Americans were sub-human, their subjugation was to be achieved through any means necessary, and whites who carried out lynchings would face no legal repercussions.”

“In America, we’re not free. We are burdened by a history of racial inequality and injustice. It compromises us. It constrains us,” Stevenson told Co.Exist. “We have to create a new relationship with this history.”

“It’s a place that will be beautiful. It’s a place,” Stevenson added, “that will tell a hard but a necessary story.”

The memorial will have a large, four-sided gallery of 801 suspended six-foot columns, according to The New York Times, each representing a county where a person or people were lynched, with an etching of their names.

The memorial will have a large, four-sided gallery of 801 suspended six-foot columns, according to The New York Times, each representing a county where a person or people were lynched, with an etching of their names.

This past February at a TED conference in Vancouver, memorial designer Michael Murphy gave a preview of the project.

“Countries like Germany and South Africa and Rwanda have found it necessary to build memorials to reflect on the atrocities of their past in order to heal their national psyche,” Murphy said, as reported by Citylab. “We have yet to do this in the United States.”

In Rwanda there is a healing process known as ubudehe, which means “community works for the community,” according to Murphy. The plan for the memorial is to collect soil from each lynching site and place the soil in each column of the memorial, as if to finally put the victims to rest — an act of “spiritual healing” and “restorative justice,” as he told Citylab.

At a time when the public is gaining awareness of the present-day killing of Black people through racial violence, it is time to also remember the names of those countless victims of lynching throughout America’s past. We must do this if we want true justice.