Black Farmers Continue Pressing USDA and Obama Administration and Supreme Court for Justice.

By Barrington M. Salmon Aug. 7, 2016

For more than two decades, Black farmers have driven tractors to Capitol Hill and walked the halls of Congress, coaxing, cajoling and confronting lawmakers.

They have also filed lawsuits, protested and demonstrated. All of this an effort to correct an admittedly egregious legacy of racism and discrimination by the US Department of Agriculture.

Despite high profiled settlements several years ago, just last month, three dozen farmers and their supporters from Georgia, North Carolina, Alabama, South Carolina, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Arkansas and Kentucky descended on the steps of the United States Supreme Court. At the rally and demonstration, the protesters promised to fight until they’re heard and one of their members, Bernice Atchison, filed a writ with the Supreme Court.

“[Former USDA Secretary Dan] Glickman acknowledged that the agency had discriminated against Black farmers. We have dealt with bias, discrimination and double standards,” said Georgia Farmer Eddie Slaughter in front of the court. “We had supervised accounts which meant they had power over our money and county loan officers discriminated against Black farmers. It’s been nothing but fraud, deceit and breach of contract. Our damages are in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. They have persecuted us and now, 35-40 percent of Black farmers have been run out of the business. They were supposed to return one and a half million acres of land to Black farmers but didn’t.”

Slaughter concluded, “We’re here to say Black farmers of 2016 are the Dred Scott of 1857. He demanded to be free. The fraud and corruption amounts to economic terrorism against Black farmers. We don’t have anyone standing up for us. The Congressional Black Caucus or President Obama could have created a national investigative commission. But they’ve done nothing. Equal justice under the law does not exist in this.”

Bernice Atchison, president of Black Farmers of Alabama, agreed as she recounted her long ordeal since the USDA seized and sold 239 acres of family land.

“My husband’s father died and they sold the land on the steps of the courthouse,” she explained as she held an armful of folders. “I’ve been fighting since 1983. I’m 78 years old. It’s been a long time for me. I have enough evidence that it would take a truck to haul it away. I walked the halls of the Capitol Hill with (the late) John Boyd, going from office-to-office.”

In 2004, Congress asked Atchison to testify before a subcommittee.

“They said my face was the face of the 66,000 Black farmers who’d been denied and said my due process had been violated,” She recalled. “Congress called me as an expert eyewitness before them and a judge gave me standing in the court. I’m the most impacted but I haven’t been paid. They’re punishing me. We’re asking for justice not a set amount.”

Atchison said she has a case on the docket that she filed in 2014. But, she says she and her colleagues have hit a brick wall.

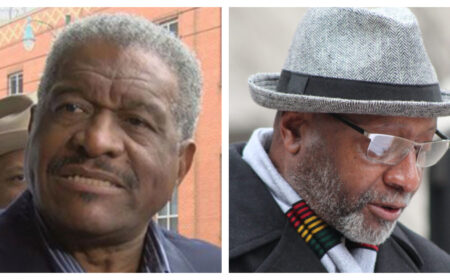

“It’s been 20 years that farmers have been saying that they’ve been mistreated and we’re still losing land,” said Gary R. Grant, president of the Black Farmers & Agriculturists Association & The Land Loss Fund. “Where we had one million farmers, that number is down to 20,000. Many farmers feel a sense of helplessness, a number are suffering from disease and health issues we’ve never dealt with such as diabetes and high blood pressure. They’re wiping us out. The land isn’t disappearing. It’s been stolen from us.”

Grant said there has been no Congressional investigation into the assortment of alleged abuses by local farm service agencies.

“Not a single employee at USDA has lost their job,” said Grant. “Between 1981 and 1996, 64 percent of Black farmers have (disappeared) and only one person was forced to retire but with full benefits.”

Repeated attempts to secure comments and reaction from the USDA were not successful. However, a 1994 USDA study examined the treatment of racial minorities and women as the agency was weathered allegations of pervasive racial discrimination in the way its employees handled applications for farm loans and grants to primarily Southern black farmers. Between 1990 and 1995, researchers found that “minorities received less than their fair share of USDA money for crop payments, disaster payments, and loans.”

The final report noted that the USDA gave corporations 65 percent of loans, while 25 percent of the largest payments went to White male farmers. Further, 97 percent of disaster payments went to White farmers, with less than 1 percent reaching black farmers.

The study highlighted “gross deficiencies” in the way the USDA collected and handled data which muddied the reasons for the discrepancies in treatment between Black and White farmers in such a manner that the reasons couldn’t easily be determined.

Carol Estes, in a story about the travails of Black farmers in a Yes! Magazine article headlined, “Second Chance for Black Farmers,” details one of the many challenges.

Estes reports, “The USDA does provide a remedy for farmers who believe they’ve been treated unfairly: They can file a claim with the agency’s civil rights complaint office in Washington, DC,” she said. “There’s a hitch, though. Ronald Reagan shut down that office in 1983, and the USDA never informed farmers. So for the next 13 years, until the office was reopened by the Clinton administration, black farmers’ complaints literally piled up in a vacant room in the Agriculture building in Washington.”

The farmers who congregated in front of the Supreme Court cited figures ranging from 14,000 to 40,000 cases they say the USDA has failed to process. The official put in charge of unblocking the bottleneck is a part of the problem because he’s made no effort to facilitate the processing of the backed up claims, they charge.

The farmers have received two settlements, Pigford I and II, class action lawsuits which together have allocated about $2.25 billion to tens of thousands of Black farmers. The first lawsuit was settled in April 1999 by US District Court Judge Paul L. Friedman. And in December 2010, Congress appropriated $1.2 billion for 70,000 additional claimants.

The judgment was the largest civil rights settlement in this country’s history. While some see the settlement as a victory, for most Black farmers it’s bitter-sweet because the settlement payments aren’t enough to buy farm equipment, give farmers long-term comfort; and in no way makes up for the destruction of rural Black communities and the theft of land by government officials, they say.

For example, the farmers detailed the travails of Eddie and Dorothy Wise, North Carolina farmers who were forced off their 106-acre farm in January by 14 heavily armed sheriffs and federal marshals. They said this happened without the couple being granted any hearing. Wise, a 67-year-old retired Green Beret and his wife, a retired grants manager, lived on their farm for more than 20 years. After being evicted, the Wises lost their property and are living in a hotel. A GoFundMe page is soliciting help for the family. Supporters have raised $6,000 toward the $50,000 goal.

“Nothing has been done to enhance the opportunities and fairness. What they’ve been doing is working to manipulate and separate the black farmer from his community where he lives, and critically himself,” said Grant.

Lawrence Lucas, who worked with the federal government for 38 years, said little has changed at the agency.

“There’s a reason why they call the USDA ‘the last plantation.’ The civil rights problems there have not been fixed,” said Lucas, president emeritus of the USDA Coalition of Minority Employees. “Ninety-seven percent of Black farmers did not get the debt relief promised in the agreement. Things are not better, which is why we have to stand up.”

The farmers said the White House, the US Department of Justice, Congress, the Congressional Black Caucus and civil rights leaders have done little to bring this long-running saga to a close.

“Cases have not been processed and no investigation has been undertaken,” Lucas said.

Oklahoma resident Muhammad Robbalaa said he was at the rally “because a fighter doesn’t quit.”

He said, “I have an older brother who lost his land in 1983. He had a stroke after we fought a battle with the State Supreme Court,” said Robbalaa, 75. “They ruled that it was other folks land and they gave it to White folks. I’m still in the cattle business and my daughters have come back and joined the business. I originally owned 250 acres of land but now I’m on leased land.”

Grant, Slaughter, Atchison and the other farmers said the government has colluded, nothing’s changed, they are further victimized and the land they own continues to be seized and stolen.

“People think that Pigford and $50,000 settled all our issues, but it hasn’t. You can’t even buy a tractor with just that,” Grant said. “They continue to take and foreclose Black farmers. The (lawsuit) assured us a hearing before foreclosure and that has not happened. All we want is justice and equality.”