Alprentice ‘Bunchy’ Carter ‘would have rode with Nat Turner

by Norman (Otis) Richmond, aka Jalali

“If Bunchy had been on the same plantation as Nat Turner, you can believe he would have rode with Nat Turner. That’s the type of person Bunchy was.” – Kumasi

Oct. 12 is the birthday of one of the most talented and promising young men martyred in the massive state repression against the Black Panther Party for Self Defense.

NBC television has resurrected Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter with a series called “Aquarius.” The imperialist media has brought back both Carter and Charles Manson. Carter was an iconic Black revolutionary from Los Angeles. Manson was a cold-blooded serial killer who led the Manson Family that murdered many in California.

Somehow Hollyweird has united these two polar opposites for television. It is not that weird when we understand that these forces are part of the state whose job it is to keep Africa, Africans and all oppressed people confused.

Gerald Horne, who wrote the volume, “Confronting Black Jacobins: The U.S., the Haitian Revolution and the Origins of the Dominican Republic,” taught Carter’s daughter Danon at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and has written extensively on Hollywood. Horne says Hollywood has done a number on Africans in America from “Birth of a Nation” to “Gone with the Wind,” depicting Black women as mammies, servants and sex objects.

Linden Beckford Jr., a graduate of Grambling University, is currently writing a biography of Carter.

Carter is almost forgotten

Unlike Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, Eldridge Cleaver and George Jackson, Carter has almost been forgotten from the history of Africans in America except for diehards.

Yes, the Fugees – Wyclef Jean, Lauryn Hill and Pras Michel – mention Carter on the 1996 soundtrack film “When We Were Kings” about the famous “Rumble in the Jungle” heavyweight championship match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, which took place in 1974. And yes, M-1 and stic man of dead prez did “B.I.G. Respect,” a song on their mixtape, “Turn off the Radio,” that mentions Carter. But that is about it.

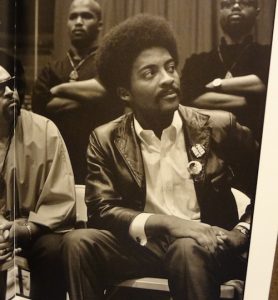

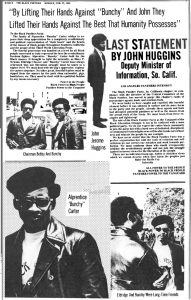

Who were Carter and John Huggins and why are they important for the 21st century? Carter, then 26 (born Oct. 12, 1942), was assassinated on Jan. 17, 1969, along with John Huggins, 23 (born Feb. 11, 1945), in a Campbell Hall classroom at UCLA in Los Angeles.

The team of Carter and Huggins are interesting for several reasons. Number one, Carter was born in Louisiana but was made in Los Angeles. Huggins was born on the other side of the country in New Haven, Connecticut. Number two, Carter was a product of the Black proletariat while Huggins was from the Black middle class.

One of Huggins’ aunts, Constance Baker Motley (Sept. 14, 1921 – Sept. 28, 2005) was an African born in America whose parents hailed from Nevis in the Caribbean. She was a lawyer, judge, state senator and borough president of Manhattan, New York City. Huggins committed class suicide and he and Carter had no problem working together.

It is a tragic coincidence in history that eight years before Carter and Huggins joined the ancestors, Patrice Emery Lumumba, the first democratically elected president of the Congo, Joseph Okito, vice president of the Senate, and Maurice Mpolo, sports and youth minister, were killed in the Congo by an unholy alliance of the CIA, Belgian imperialism and other agents of imperialism headed by Mobuto Sese Seko Ngbendu Wa Za Banga, aka Col. Joseph Mobuto, on Jan. 17, 1961.

Carter and Huggins were gunned down by members of the cultural nationalist US Organization. An FBI memo dated Nov. 29, 1968, described a letter that the Los Angeles FBI office intended to mail to the Black Panther Party office.

This letter, which was made to appear as if it had come from the US Organization, described fictitious plans by US to ambush BPP members. The FBI memo stated, “It is hoped this counterintelligence measure will result in an ‘US’ and BPP vendetta.”

Many feel that the leader of US, Ron Karenga, was working for the other side. An article in the Wall Street Journal described Karenga as a thriving businessman, specializing in gas stations, who maintained close ties to Eastern Rockefeller family and LA’s mayor.

Michael Newton pointed out in the volume, “Bitter Grain: Huey P. Newton and the Black Panther Party,” a Wall Street Journal article which reported: “A few weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King … Mr. Karenga slipped into Sacramento for a private chat with Gov. Reagan, at the governor’s request. The Black nationalist also met clandestinely with Los Angeles police chief Thomas Reddin after Mr. King was killed.”

We need some stronger stuff

At that moment in history, many cultural nationalists maintained that the cultural revolution must take place before a political one could proceed. Huey P. Newton, the co-founder of the Black Panther Party, countered with the view: “We believe that culture itself will not liberate us. We’re going to need some stronger stuff.”

The Black Panther Party led by Newton and Bobby Seale was like the African National Congress of South Africa (ANC). It was an anti-imperialist alliance; many like Carter embraced revolutionary nationalism while others like Newton, George Jackson and Fred Hampton took a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist (MLM) position. Hampton openly said he was fighting for socialism leading to communism.

Carter named Geronimo

Carter was a firm supporter of the Native American struggle. It was Carter who changed Elmer Pratt into Geronimo ji-Jaga Pratt (Sept. 13, 1947 – June 2, 2011) after the great Native American warrior Geronimo, “the one who yawns” (June 1829 – Feb. 17, 1909) was a prominent Apache leader who fought against Mexico and Arizona for their expansion into Apache tribal lands for several decades during the Apache Wars.

Geronimo replaced Carter as the deputy minister of defense of the Southern California Chapter of the BPP after Carter was taken out. Carter left a memo saying his wish was for Geronimo to replace him.

Carter was never known as an anti-Communist. Before joining the Black Panther Party, Carter was recruited by Raymond “Maasi” Hewitt to a Maoist study group called the Red Guard. I was a part of the same group; however, Carter came in after I left Los Angeles.

Carter was influenced by Jean-Jacques Dessalines of Haiti and Dedan Kimathi of the Land and Freedom Army, the so-called Mau Mau. The Los Angeles Chapter under Bunchy’s leadership required that members take the Mau Mau Oath. Here is the Mau Mau Oath:

“I speak the truth and vow before God / And before this movement, / The movement of Unity, / The Unity which is put to the test, / The Unity that is mocked with the name of ‘Mau Mau,’ / That I shall go forward to fight for the land, / The lands of Kirinyaga that we cultivated, / The lands which were taken by the Europeans, / And if I fail to do this, / May this oath kill me, / May this seven kill me, / May this meat kill me.”

Days at Los Angeles City College

Carter and a small segment of people who lived in my area of Los Angeles had an international world view. He was a legendary figure in my neighborhood. After he was released from prison, he attended Los Angeles City College. Carter was my senior and I didn’t meet him until he was released from jail.

He and others, like Sigidi Abdullah and his S.O.S Band, “Take Your Time (Do It Right)”; Rhongea Southern, now Daar Malik El-Bey, who worked closely with Abdullah; Earl Randall, who went on to work with Willie Mitchell at Hi Records and wrote Al Green’s “God Bless Our Love”; Fred Goree, who became Masai Karega Kenyatta and a DJ on WCHB 1440AM in Detroit, went to LACC at the same time.

Sigidi told me that Carter asked him to organize a talent show at LACC. I remember singing the Spinners’ “I’ll Always Love You” at this event. El-Bey was my guitarist.

Carter’s political consciousness was raised before he joined the Black Panther Party. Kumasi, who Huey P. Newton asked to replace Carter as the leader of the Southern California Chapter of the BPP, talked to me about the LA legend.

Says Kumasi: “When Malcolm X first came to Los Angeles, he built the first outpost right there in our neighborhood. The Mosque (Temple 27) itself was close to us and all of us had visited the Mosque. As a matter of fact, Bunchy and many of the Renegade Slausons (Bunchy had his own set of Slausons inside the Slausons) were the first youth Fruit of Islam (FOI) in LA. Carter was only 15 years old at that moment in history.

Carter was a 20th century renaissance man. He was great at many things and was a poet and a singer. Elaine Brown has written that many Panthers sang together: “John (Huggins) sang bass to my contralto and Bunchy’s falsetto.”

Brown pointed out in her autobiography, “A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story,” how the trio used to sing the Young Hearts’ “I’ve Got Love for My Baby.” He was also a great dancer. David Hilliard maintains that if it were not for racism, Carter may have become an Olympic swimmer.

Brown says while all this is true, Carter was first and foremost a revolutionary. This is extraordinary if you consider that Carter suffered a childhood bout of polio and moved to South Central LA, where his mother, Nola Carter, enrolled him in a “therapeutic” dance class.

Carter’s Louisiana-born mother is still in the land of the living at the time of this writing. She is almost a century old and has lost two sons: Arthur Morris, Carter’s older step brother, acted as Carter’s bodyguard and was the first member of the BPP to lose his life. He was killed in March of 1968. Little Bobby Hutton, who was influenced by Carter, was killed on April 6, 1968. Her youngest son, Kenneth Fati Carter, is currently locked down in Corcoran State Prison in California.

Caffee Greene, mother of Raymond Nat Turner, Black Agenda Report’s poet-in-residence, hired Carter to work at the Teen Post in Los Angeles. Greene first hired Raymond “Masai” Hewitt, who was replaced by Carter. It was at the Teen Post that I first heard Eldridge Cleaver speak. Cleaver and Carter were both Nation of Islam ministers in prison.

Turner saw the cultural side of Carter: “Yeah, I heard Bunchy sing Stevie’s ‘I’m Wondering’ and ‘I Was Made to Love Her,’ and I used to hear Tommy (Lewis) play piano at the Teen Post my mom directed. … It was also fun to watch Bunchy dance – Philly Dog, Jerk and Twine … a lil’ ‘Bitter Dog’ with the Philly Dog every once in a while … ‘Bebop Santa from the Cool North Pole’ and ‘Black Mother’ were also great to hear.” Tommy Lewis, Robert Lawrence and Steve Bartholomew were murdered by the Los Angeles police at a service station on Aug. 25, 1968.

Kumasi opines that Carter and George Jackson were like Henri Christophe and Jean-Jacques Dessalines. While they were well-versed in history, revolutionary theory and current events, both were soldiers ready to take to the battlefield. Carter made a contribution to Africa, Africans and oppressed humanity. We should remember him every Oct. 12.

Post script

In his Executive Order No. 1, “The Correct Handling of Differences Between Black Organizations,” issued in 1968, Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, then the deputy minister of defense of the Southern California Chapter at Los Angeles of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, wrote: “Let this be heard: The Black Panther Party must never be the enemy of the people. The Black Panther Party must never put itself in that other organizations can make them seem to be the enemy of Black People …

“History will show we have the correct analysis of the problem. The people will relate to the party that relates to them. Therefore, we must continue to relate to the people. Therefore, we do not get into squabbles with other Black organizations; we do not have time for this when engaging in revolution. Let this be done.”

Norman (Otis) Richmond, aka Jalali, was born in Arcadia, Louisiana, and grew up in Los Angeles. He left Los Angles after refusing to fight in Vietnam because he felt that, like the Vietnamese, Africans in the United States were colonial subjects. In the 1960s, Richmond moved to Toronto, where he co-founded the Afro American Progressive Association, one of the first Black Power organizations in that part of the world. Before moving to Toronto permanently, Richmond worked with the Detroit-based League of Revolutionary Black Workers. He was the youngest member of the central staff. When the League split, he joined the African People’s Party. In 1992, Richmond received the Toronto Arts Award. In front of an audience that included the mayor of Toronto, Richmond dedicated his award to Mumia Abu-Jamal, Assata Shakur, Geronimo Pratt, the African National Congress of South Africa and Fidel Castro and the people of Cuba. In 1984 he co-founded the Toronto Chapter of the Black Music Association with Milton Blake. Richmond began his career in journalism at the African Canadian weekly Contrast. He went on to be published in the Toronto Star, the Toronto Globe & Mail, the National Post, the Jackson Advocate, Share, the Islander, the Black American, Pan African News Wire, and Black Agenda Report. Internationally, he has written for the United Nations, the Jamaican Gleaner, the Nation (Barbados) and Pambazuka News. Currently, he produces Diasporic Music, a radio show for Uhuru Radio, and writes a column, Diasporic Music, for The Burning Spear newspaper. For more information, contact him at norman.o.richmond@gmail.com