The Great Land Robbery: The shameful story of how 1 million black families have been ripped from their farms

I. Wiped Out

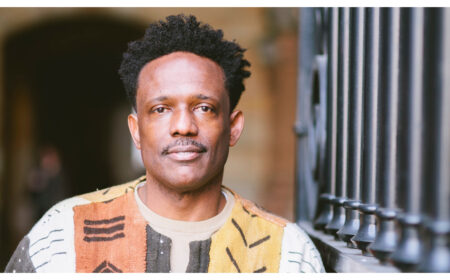

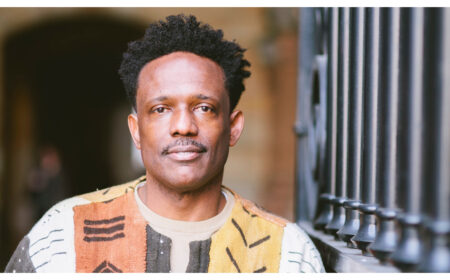

“You ever chop before?” Willena Scott-White was testing me. I sat with her in the cab of a Chevy Silverado pickup truck, swatting at the squadrons of giant, fluttering mosquitoes that had invaded the interior the last time she opened a window. I was spending the day with her family as they worked their fields just outside Ruleville, in Mississippi’s Leflore County. With her weathered brown hands, Scott-White gave me a pork sandwich wrapped in a grease-stained paper towel. I slapped my leg. Mosquitoes can bite through denim, it turns out.

Cotton sowed with planters must be chopped—thinned and weeded manually with hoes—to produce orderly rows of fluffy bolls. The work is backbreaking, and the people who do it maintain that no other job on Earth is quite as demanding. I had labored long hours over other crops, but had to admit to Scott-White, a 60-something grandmother who’d grown up chopping, that I’d never done it.

“Then you ain’t never worked,” she replied.

The fields alongside us as we drove were monotonous. With row crops, monotony is good. But as we toured 1,000 acres of land in Leflore and Bolivar Counties, straddling Route 61, Scott-White pointed out the demarcations between plots. A trio of steel silos here. A post there. A patch of scruffy wilderness in the distance. Each landmark was a reminder of the Scott legacy that she had fought to keep—or to regain—and she noted this with pride. Each one was also a reminder of an inheritance that had once been stolen.

Drive Route 61 through the Mississippi Delta and you’ll find much of the scenery exactly as it was 50 or 75 years ago. Imposing plantations and ramshackle shotgun houses still populate the countryside from Memphis to Vicksburg. Fields stretch to the horizon. The hands that dig into black Delta dirt belong to people like Willena Scott-White, African Americans who bear faces and names passed down from men and women who were owned here, who were kept here, and who chose to stay here, tending the same fields their forebears tended.

But some things have changed. Back in the day, snow-white bolls of King Cotton reigned. Now much of the land is green with soybeans. The farms and plantations are much larger—industrial operations with bioengineered plants, laser-guided tractors, and crop-dusting drones. Fewer and fewer farms are still owned by actual farmers. Investors in boardrooms throughout the country have bought hundreds of thousands of acres of premium Delta land. If you’re one of the millions of people who have a retirement account with the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association, for instance, you might even own a little bit yourself.

A war waged by deed of title has dispossessed 98 percent of black agricultural landowners in America.

TIAA is one of the largest pension firms in the United States. Together with its subsidiaries and associated funds, it has a portfolio of more than 80,000 acres in Mississippi alone, most of them in the Delta. If the fertile crescent of Arkansas is included, TIAA holds more than 130,000 acres in a strip of counties along the Mississippi River. And TIAA is not the only big corporate landlord in the region. Hancock Agricultural Investment Group manages more than 65,000 acres in what it calls the “Delta states.” The real-estate trust Farmland Partners has 30,000 acres in and around the Delta. AgriVest, a subsidiary of the Swiss bank UBS, owned 22,000 acres as of 2011. (AgriVest did not respond to a request for more recent information.)

Unlike their counterparts even two or three generations ago, black people living and working in the Delta today have been almost completely uprooted from the soil—as property owners, if not as laborers. In Washington County, Mississippi, where last February TIAA reportedly bought 50,000 acres for more than $200 million, black people make up 72 percent of the population but own only 11 percent of the farmland, in part or in full. In Tunica County, where TIAA has acquired plantations from some of the oldest farm-owning white families in the state, black people make up 77 percent of the population but own only 6 percent of the farmland. In Holmes County, the third-blackest county in the nation, black people make up about 80 percent of the population but own only 19 percent of the farmland. TIAA owns plantations there, too. In just a few years, a single company has accumulated a portfolio in the Delta almost equal to the remaining holdings of the African Americans who have lived on and shaped this land for centuries.

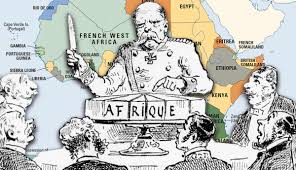

This is not a story about TIAA—at least not primarily. The company’s newfound dominance in the region is merely the topsoil covering a history of loss and legally sanctioned theft in which TIAA played no part. But TIAA’s position is instrumental in understanding both how the crimes of Jim Crow have been laundered by time and how the legacy of ill-gotten gains has become a structural part of American life. The land was wrested first from Native Americans, by force. It was then cleared, watered, and made productive for intensive agriculture by the labor of enslaved Africans, who after Emancipation would come to own a portion of it. Later, through a variety of means—sometimes legal, often coercive, in many cases legal and coercive, occasionally violent—farmland owned by black people came into the hands of white people. It was aggregated into larger holdings, then aggregated again, eventually attracting the interest of Wall Street.

Owners of small farms everywhere, black and white alike, have long been buffeted by larger economic forces. But what happened to black landowners in the South, and particularly in the Delta, is distinct, and was propelled not only by economic change but also by white racism and local white power. A war waged by deed of title has dispossessed 98 percent of black agricultural landowners in America. They have lost 12 million acres over the past century. But even that statement falsely consigns the losses to long-ago history. In fact, the losses mostly occurred within living memory, from the 1950s onward. Today, except for a handful of farmers like the Scotts who have been able to keep or get back some land, black people in this most productive corner of the Deep South own almost nothing of the bounty under their feet.

II. “Land Hunger”

Land has always been the main battleground of racial conflict in Mississippi. During Reconstruction, fierce resistance from the planters who had dominated antebellum society effectively killed any promise of land or protection from the Freedmen’s Bureau, forcing masses of black laborers back into de facto bondage. But the sheer size of the black population—black people were a majority in Mississippi until the 1930s—meant that thousands were able to secure tenuous footholds as landowners between Emancipation and the Great Depression.

Driven by what W. E. B. Du Bois called “land hunger” among freedmen during Reconstruction, two generations of black workers squirreled away money and went after every available and affordable plot they could, no matter how marginal or hopeless. Some found sympathetic white landowners who would sell to them. Some squatted on unused land or acquired the few homesteads available to black people. Some followed visionary leaders to all-black utopian agrarian experiments, such as Mound Bayou, in Bolivar County.

From March 1901: W. E. B. Du Bois’s ‘The Freedmen’s Bureau’

It was never much, and it was never close to just, but by the early 20th century, black people had something to hold on to. In 1900, according to the historian James C. Cobb, black landowners in Tunica County outnumbered white ones three to one. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, there were 25,000 black farm operators in 1910, an increase of almost 20 percent from 1900. Black farmland in Mississippi totaled 2.2 million acres in 1910—some 14 percent of all black-owned agricultural land in the country, and the most of any state.

The foothold was never secure. From the beginning, even the most enterprising black landowners found themselves fighting a war of attrition, often fraught with legal obstacles that made passing title to future generations difficult. Bohlen Lucas, one of the few black Democratic politicians in the Delta during Reconstruction (most black politicians at the time were Republicans), was born enslaved and managed to buy a 200-acre farm from his former overseer. But, like many farmers, who often have to borrow against expected harvests to pay for equipment, supplies, and the rent or mortgage on their land, Lucas depended on credit extended by powerful lenders. In his case, credit depended specifically on white patronage, given in exchange for his help voting out the Reconstruction government—after which his patrons abandoned him. He was left with 20 acres.

In Humphreys County, Lewis Spearman avoided the pitfalls of white patronage by buying less valuable wooded tracts and grazing cattle there as he moved into cotton. But when cotton crashed in the 1880s, Spearman, over his head in debt, crashed with it.

Around the turn of the century, in Leflore County, a black farm organizer and proponent of self-sufficiency—referred to as a “notoriously bad Negro” in the local newspapers—led a black populist awakening, marching defiantly and by some accounts bringing boycotts against white merchants. White farmers responded with a posse that may have killed as many as 100 black farmers and sharecroppers along with women and children. The fate of the “bad Negro” in question, named Oliver Cromwell, is uncertain. Some sources say he escaped to Jackson, and into anonymity.

Like so many of his forebears, Ed Scott Sr., Willena Scott-White’s grandfather, acquired his land through not much more than force of will. As recorded in the thick binders of family history that Willena had brought along in the truck, and that we flipped through between stretches of work in the fields, his life had attained the gloss of folklore. He was born in 1886 in western Alabama, a generation removed from bondage. Spurred by that same land hunger, Scott took his young family to the Delta, seeking opportunities to farm his own property. He sharecropped and rented, and managed large farms for white planters, who valued his ability to run their sprawling estates. One of these men was Palmer H. Brooks, who owned a 7,000-acre plantation in Mississippi’s Leflore and Sunflower Counties. Brooks was uncommonly progressive, encouraging entrepreneurship among the black laborers on his plantation, building schools and churches for them, and providing loans. Scott was ready when Brooks decided to sell plots to black laborers, and he bought his first 100 acres.

Unlike Bohlen Lucas, Scott largely avoided politics. Unlike Lewis Spearman, he paid his debts and kept some close white allies—a necessity, since he usually rejected government assistance. And unlike Oliver Cromwell, he led his community under the rules already in place, appearing content with what he’d earned for his family in an environment of total segregation. He leveraged technical skills and a talent for management to impress sympathetic white people and disarm hostile ones. “Granddaddy always had nice vehicles,” Scott-White told me. They were a trapping of pride in a life of toil. As was true in most rural areas at the time, a new truck was not just a flashy sign of prosperity but also a sort of credit score. Wearing starched dress shirts served the same purpose, elevating Scott in certain respects—always within limits—even above some white farmers who drove into town in dirty overalls. The trucks got shinier as his holdings grew. By the time Scott died, in 1957, he had amassed more than 1,000 acres of farmland.

Scott-White guided me right up to the Quiver River, where the legend of her family began. It was a choked, green-brown gurgle of a thing, the kind of lazy waterway that one imagines to be brimming with fat, yawning catfish and snakes. “Mr. Brooks sold all of the land on the east side of this river to black folks,” Scott-White told me. She swept her arm to encompass the endless acres. “All of these were once owned by black families.”

III. The Great Dispossession

That era of black ownership, in the Delta and throughout the country, was already fading by the time Scott died. As the historian Pete Daniel recounts, half a million black-owned farms across the country failed in the 25 years after 1950. Joe Brooks, the former president of the Emergency Land Fund, a group founded in 1972 to fight the problem of dispossession, has estimated that something on the order of 6 million acres was lost by black farmers from 1950 to 1969. That’s an average of 820 acres a day—an area the size of New York’s Central Park erased with each sunset. Black-owned cotton farms in the South almost completely disappeared, diminishing from 87,000 to just over 3,000 in the 1960s alone. According to the Census of Agriculture, the racial disparity in farm acreage increased in Mississippi from 1950 to 1964, when black farmers lost almost 800,000 acres of land. An analysis for The Atlantic by a research team that included Dania Francis, at the University of Massachusetts, and Darrick Hamilton, at Ohio State, translates this land loss into a financial loss—including both property and income—of $3.7 billion to $6.6 billion in today’s dollars.

This was a silent and devastating catastrophe, one created and maintained by federal policy. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal life raft for agriculture helped start the trend in 1937 with the establishment of the Farm Security Administration, an agency within the Department of Agriculture. Although the FSA ostensibly existed to help the country’s small farmers, as happened with much of the rest of the New Deal, white administrators often ignored or targeted poor black people—denying them loans and giving sharecropping work to white people. After Roosevelt’s death, in 1945, conservatives in Congress replaced the FSA with the Farmers Home Administration, or FmHA. The FmHA quickly transformed the FSA’s programs for small farmers, establishing the sinews of the loan-and-subsidy structure that undergirds American agriculture today. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy’s administration created the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service, or ASCS, a complementary program to the FmHA that also provided loans to farmers. The ASCS was a federal effort—also within the Department of Agriculture—but, crucially, the members of committees doling out money and credit were elected locally, during a time when black people were prohibited from voting.

Through these programs, and through massive crop and surplus purchasing, the USDA became the safety net, price-setter, chief investor, and sole regulator for most of the farm economy in places like the Delta. The department could offer better loan terms to risky farmers than banks and other lenders, and mostly outcompeted private credit. In his book Dispossession, Daniel calls the setup “agrigovernment.” Land-grant universities pumped out both farm operators and the USDA agents who connected those operators to federal money. Large plantations ballooned into even larger industrial crop factories as small farms collapsed. The mega-farms held sway over agricultural policy, resulting in more money, at better interest rates, for the plantations themselves. At every level of agrigovernment, the leaders were white.

READ MORE AT: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/09/this-land-was-our-land/594742/