WE MUST NEVER FORGET!!!

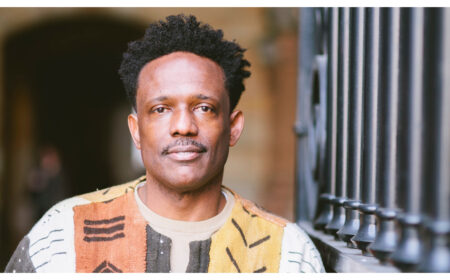

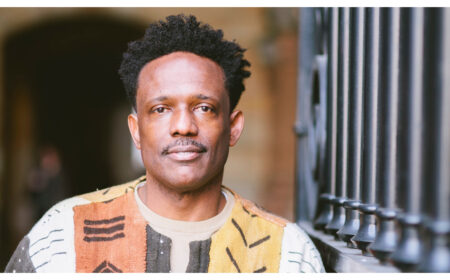

DENMARK VESEY 1767 – July 2, 1822

The date of Denmark Vesey’s birth remains uncertain (it was probably around 1767), as does his past before 1781. He was either born in Africa or as a slave on St. Thomas, an island in the West Indies. The island became a center for the slave trade and for the growing of sugar and cotton. Over 4,000 black people and under 400 whites lived there in the late 1700s.

In 1781, when he was about fourteen, Denmark was bought by a slaver called Captain Joseph Vesey, who was struck by his good looks and intelligence. Denmark, as he was called, was one of 390 slaves whom Captain Vesey brought from St. Thomas to Haiti, then a French colony called Saint-Domingue. There the boy was sold and put to work in a sugar plantation.

Cutting and pulping sugar cane is hard and exhausting work even for a grown man, but Denmark did not remain at it for long. One day, he surprised his fellow slaves and annoyed his new master by falling to the ground in an epileptic fit. A slave who suffered from epilepsy was of little use on a plantation, so Denmark’s master returned him to Captain Vesey when the captain next called at Saint-Domingue. The boy was unsound goods, he said.

Since Denmark was not suited to heavy labor, the captain made him his personal servant, and during the next two years Denmark saw many of the horrors of the slave trade as he sailed with the captain on his voyages between Africa and the West Indies. When in 1783 the captain decided to give up his slaving voyages and settle in Charleston, South Carolina, Denmark went with him. He remained the captain’s slave for the next seventeen years.

As a personal slave, Denmark Vesey lived a comparatively comfortable life — far better than slaves working on plantations — and he had a certain amount of freedom to come and go as he pleased. Nevertheless, he was still a slave, subject to the whims of his master, and his first thought when he won $1,500 in a lottery in 1800 was to buy his freedom. He paid his master $600, and with the rest of his winnings he set up a carpentry shop.

Vesey proved to be a highly skilled carpenter, and his business did so well that he grew quite wealthy. In 1816, he and other free blacks established a separate black Methodist church in Charleston. By 1820, the church had about 3,000 members. Vesey was a minister of the church and, with his growing family of children and his comfortable house on Bull Street, he was viewed as a respectable member of the community. And so he was. But he had other things on his mind, too.

Since living in Saint-Domingue in his youth, Vesey had followed the events there with interest, and he was thrilled when he heard about the great uprising of slaves in 1791. He was even more thrilled when the slaveowners fled and the black people of the former colony took control. In 1804, Saint-Domingue became the independent nation of Haiti.

Here was a success story to fire the imagination. If the slaves of Saint-Domingue could triumph over their masters, why not the slaves of South Carolina? Why not those throughout the South? Vesey was aware that previous attempts at rebellion had been put down mercilessly, but the events in Haiti gave him new hope. As he thundered from the pulpit each Sunday, he began to sow the seeds of rebellion. He urged his congregation to break free from slavery, and he quoted verses from the Bible to give them encouragement. He spoke to workers in the plantations and on street corners, reading aloud from antislavery pamphlets written by whites. He even argued with whites who supported slavery — an activity that always drew an admiring and awestruck black audience

Four years after it was opened, the black Methodist Church in Charleston was closed down by the whites. Vesey and many others responded with anger and an intensified desire to fight slavery. As Vesey traveled from place to place spreading his message, the black people of the Charleston area began to look upon him as a savior, and he had no difficulty gathering recruits when he started to organize his war of liberation. By 1822, he had a carefully arranged plan of battle and had chosen four dependable lieutenants: Ned and Rolla Bennett, who were slaves of the governor: Peter Poyas, a ship’s carpenter; and Gullah Jack, who was widely believed to be bulletproof. Vesey had also gathered a supply of weapons, which he obtained from supporters in Haiti.

Vesey chose Sunday, July 14, as the day of the uprising, because the plantation hands could come to town on a Sunday without arousing suspicion. By the end of May, he and his four lieutenants had recruited a secret army of slaves and free blacks that was said to have numbered about nine thousand. They planned to strike at midnight, when they would seize the guardhouse and other key points, and block all the bridges. Meanwhile, a group of horsemen would gallop through the town killing whites to prevent them giving the alarm. Every detail was carefully worked out, and Vesey felt they stood a good chance of taking over Charleston.

Knowing how loyal household slaves could be to their masters, Vesey had ordered that none should be included in the plot. But the planned attack involved so many people that some house slaves did hear about it. One of them told his master. The authorities immediately were on the alert. Vesey responded by pushing the date of the rising forward to mid-June, but no sooner had he informed his followers than this date was betrayed too. Suddenly, Charleston was bristling with soldiers, with patrols roaming the streets and guards at every bridge.

When Vesey realized that nothing could be done, he burned all lists of names and sent his followers home, but too many people knew who the leaders were. During the next few weeks, hundreds were rounded up, including Vesey, who was captured after a two-day search.

The Trials

During lengthy trials after the insurrection had been thwarted, the intricate plans of a massive uprising emerged in the testimony. Vesey and the other leaders, according to the testimony, had instructed their forces to kill all white people instantly, as had been done in Saint-Domingue. One fact stunned the white citizens of South Carolina and did not surprise the blacks at all: every black person, slave or not, who was approached about the uprising gave it their blessing and cooperation, even though it generally meant killing the families they had been working for. The number of people included in the plan was said to number anywhere from 6,000 to 9,000 by witnesses. The court, however, proclaimed that all who had been involved had been brought to trial, limiting the conspiracy to a couple hundred people and significantly changing the nature of what actually happened for public record.

When questioned about why he, as a free man, would take such risks for a slave uprising, Vesey answered both that it was because of the general outrage to blacks imposed by slavery, and also that he hoped to free his own children from the bonds of slavery.

The Execution

Denmark Vesey was condemned to death. Although some of his followers were released, forty-three were deported and thirty-five were hanged. Five slaves were hanged along with Vesey in Charleston early in the morning on July 2. Federal troops were called out that day because of a large demonstration by black supporters. Despite beatings and arrests, the black crowds openly mourned for the leaders of the conspiracy.

The immediate effect of Vesey’s insurrection was that life became far worse for the black population of South Carolina. In a panic, the state assembly passed strict new laws limiting the movements of slaves and preventing free blacks from entering the ports.

The hysteria and fear fomented amongst the minority white population fanned the flames of the fear of future slave insurrection. In response to the Vesey conspiracy, the South Carolina Association was formed to provide more effective control of the black population. The African Church building was ordered destroyed by city authorities.

Sandy Vesey, one of Denmark’s sons, was transported, probably to Cuba. Vesey’s last wife Susan later emigrated to Liberia. Another son, Robert Vesey, survived to rebuild Charleston’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1865.

Comment (1)

Jahman

I Wish Everyday I Can Read Abt My Rich History Like Dis One.Gih Thx Admin