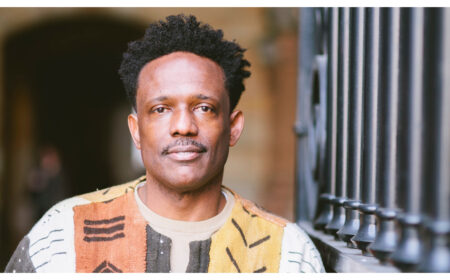

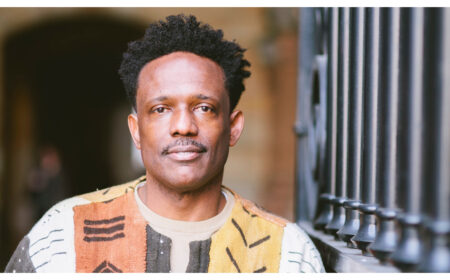

Nate Parker stars in this searingly impressive account of the Nat Turner slave rebellion.

It speaks to his ambition that the writer, director, producer and actor Nate Parker chose to title his slavery drama “The Birth of a Nation,” though the film would be a significant achievement by any name. Arriving more than a century after D.W. Griffith’s epic lit up the screen with racist images forever destined to rankle and provoke, this powerfully confrontational account of Nat Turner’s life and the slave rebellion he led in 1831 seeks to purify and reclaim a motion-picture medium that has only just begun to treat America’s “peculiar institution” with anything like the honesty it deserves. If “12 Years a Slave” felt like a breakthrough on that score, then Parker’s more conventionally told but still searingly impressive debut feature pushes the conversation further still: A biographical drama steeped equally in grace and horror, it builds to a brutal finale that will stir deep emotion and inevitable unease. But the film is perhaps even more accomplished as a theological provocation, one that grapples fearlessly with the intense spiritual convictions that drove Turner to do what he had previously considered unthinkable.

Certain to be the most widely discussed and rousingly received film in the U.S. dramatic competition at Sundance this year, “The Birth of a Nation” comes to us at a particularly fortuitous cultural moment; not unlike “12 Years a Slave” and “Selma” before it, the movie occupies that rare space where our ongoing conversation about racial injustice converges with the film industry’s slow-dawning awareness of the lack of diversity in its ranks. As a result, this artfully modulated but fitfully grueling picture presents both an obvious challenge and a potentially rich commercial prospect for a distributor willing to match Parker’s passion with its own. Careful positioning, too, will be needed to target open-minded faith-based audiences, and also to address the inevitable backlash in some quarters, given that the film presents its climactic violence in complicated but unmistakably heroic terms.

No film worthy of this particular historical subject could hope or expect to avoid controversy, and Parker’s well-researched screenplay offers its own bold take on the widely contested narrative of Turner, a Virginia-born slave and Baptist preacher who led the uprising that claimed 60 white lives and led to the killings of 200 blacks in retaliation, and served as a crucial moment of insurrection en route to the Civil War three decades later. But “The Birth of a Nation” commences long before those fateful events, with a series of scenes observing the Nat’s childhood on a cotton plantation in Southampton County, Va., owned by the white Turner family from which the boy took his surname.

In opening and recurring scenes that remind us of the land and traditions from which these black men and women were uprooted, young Nat (Tony Espinosa) experiences eerie dreams of his African ancestors, anointing him as a future leader and prophet as marked by the circular scars on his chest. “It’s not real,” his mother (Aunjanue Ellis) tells him when he awakens from one of these startling visions, though there’s no relief from the nightmare of their everyday reality — and as it is, they have a somewhat easier time than many of the other plantation slaves in Southampton County. Nat is allowed to run and play with the young Turner heir, Samuel (Griffin Freeman), and he’s treated kindly by Samuel’s mother, Elizabeth (Penelope Ann Miller), who, upon discovering that Nat can read, encourages his studies by giving him a Bible.

Years later, despite having grown up picking cotton alongside his family in the fields, Nat (now played by Parker, superbly) is a soulful preacher with enough of a rapport with his master Samuel (Armie Hammer) to persuade him to buy a young slave, Cherry (Aja Naomi King), sparing her from a fate even worse than what she’s already endured. Cherry is brought to the plantation, and before long she and Nat fall in love, marry and have a daughter, in scenes that afford a warm glimpse of their close-knit, God-fearing community. Far from sentimentalizing their experience, however, these moments offer only fleeting respite from a life of continual hardship and menace, whether it’s Nat making the mistake of addressing a white woman, or Cherry falling into the hands of the cruel Raymond Cobb (a terrifying Jackie Earle Haley), with devastating consequences.

It’s no surprise the white slaveowners are getting antsy, with talk of insurrection and rumors of violence in the air. Spying an opportunity, the sleazy, self-interested Rev. Walthall (Mark Boone Jr.) convinces Samuel to rent Nat out to other plantations as a visiting preacher, as many slaveowners will pay good money to have a black man address his fellow brothers and sisters, and hopefully quell any revolutionary impulses with a gospel of peace (aka subservience). What makes this development so bracingly ironic is that it’s Nat’s exposure to the appalling mistreatment of blacks in other parts of Virginia that convinces him a few encouraging sermons will no longer be enough. After a borderline-unwatchable scene in which he sees a slave being brutally tortured and force-fed, Nat experiences a reawakening. “I pray you sing to the Lord a new song,” he instructs his humble congregation, and it’s clear that he means to take his own advice.

Parker demonstrates a fine touch with actors (Dwight Henry, Esther Scott, Roger Guenveur Smith and Gabrielle Union round out the excellent cast), and his command of mise-en-scene would be impressive even coming from a more seasoned filmmaker. While the movie was shot entirely on location in Savannah, Ga., the visual reconstruction of antebellum Virginia is outstanding: From the drooping willows and white plantation houses of Geoffrey Kirkland’s production design to the muted, bluish cast of Elliot Davis’ widescreen compositions, the movie offers a vision at once nightmarish and painterly. As edited with measured intelligence by Steven Rosenblum (with the exception of one too-slick montage) and set to the stirring if sometimes overly vigorous accompaniment of Henry Jackman’s score, these images conspire to lure us into a world even when the barbarism pushes us away.

But the film’s most resonant element isn’t its physical realization so much as its spiritual and intellectual acuity, and it skillfully draws us into Nat’s endless internal debate as he presses himself and God about his next course of action. If “12 Years a Slave” astutely mapped out both the ruthless economic machinery of American slavery and the complicity of white Christians who used the Bible to cow their slaves into silence, then “The Birth of a Nation” delves even further into this unholy nexus of capitalism and religion, and Parker’s performance becomes a study in escalating outrage. A figure of warm, earthy saintliness for much of the movie, the actor (“Beyond the Lights,” “Arbitrage”) slowly traces Turner’s moral hardening by incremental degrees, driven by his deepening engagement with Scripture (“Do not become slaves to men,” he quotes at one point, and some believers in the audience might well also turn to “Faith without works is dead”). But he is also driven by his own worsening mistreatment at the hands of Samuel, whom Hammer convincingly embodies as a man whose decency turns out to be strictly conditional.

Turner’s own shift from Christlike grace to Jehovah-style wrath is not without its heavy-handed moments: One crucial scene, in particular, would play infinitely better without the obtrusive positioning of a stained-glass window, and the cutaways to Turner’s ancestral visions begin to verge on kitsch. But at its core, this is as intelligent and probing an inquiry into the uses and abuses of organized religion as we’ve seen in recent American movies, and also the rare slavery drama in which it’s the ideas, far more than the whipping and lynching scenes, that provide the deepest impact. Historians will have a field day debating the accuracy of the man’s dramatic trajectory (as they have since even before the publication of William Styron’s much-disputed 1967 novel, “The Confessions of Nat Turner”), and the urge to contradict a black filmmaker’s interpretation of history will of course be a hard one for many commentators to resist.

The most vigorous discussion will center on the film’s ferocious, frustrating and inescapably cathartic climax, in which the tremendous strengths of its classical storytelling, as well as its dramatic lapses, stand in perhaps the sharpest relief. Parker’s filmmaking suddenly shifts into the brutal, blood-soaked idiom of the war movie, in which various shades of moral gray are resolved in a queasy eruption of red (at the first Sundance screening, the applause that greeted certain killings proved as telling as the anxious hush that followed others). The Christ-figure overtones hover ever more stirringly, and disturbingly, over the movie’s final moments, and you may be forgiven if your mind drifts for a moment toward “Braveheart.” The movie can be forgiven as well. “The Birth of a Nation” exists to provoke a serious debate about the necessity and limitations of empathy, the morality of retaliatory violence, and the ongoing black struggle for justice and equality in this country. It earns that debate and then some.

Justin Chang

Chief Film Critic